BOSTON (CN) — Fighting to control the copyright of “The Game of Life,” the heirs of a board game designer spun the wheel Tuesday in the First Circuit, but it was unclear whether they were headed for the Poor Farm or Millionaire Acres.

In a case in which the average age of the three principal witnesses was 90, the judges seemed perplexed as the plaintiffs’ lawyer, Robert Pollaro of Cadwalader in Manhattan, accused the other side of lying under oath and inventing new theories at the last minute.

One witness used “words untethered to any facts,” and an opposing lawyer engaged in “trial by ambush,” Pollaro argued.

The key issue in the briefs was whether the Supreme Court had changed how works for hire are determined under copyright law. With the lawyers’ conflicting factual accusations dominating oral arguments Tuesday, however, the judges never even reached the question.

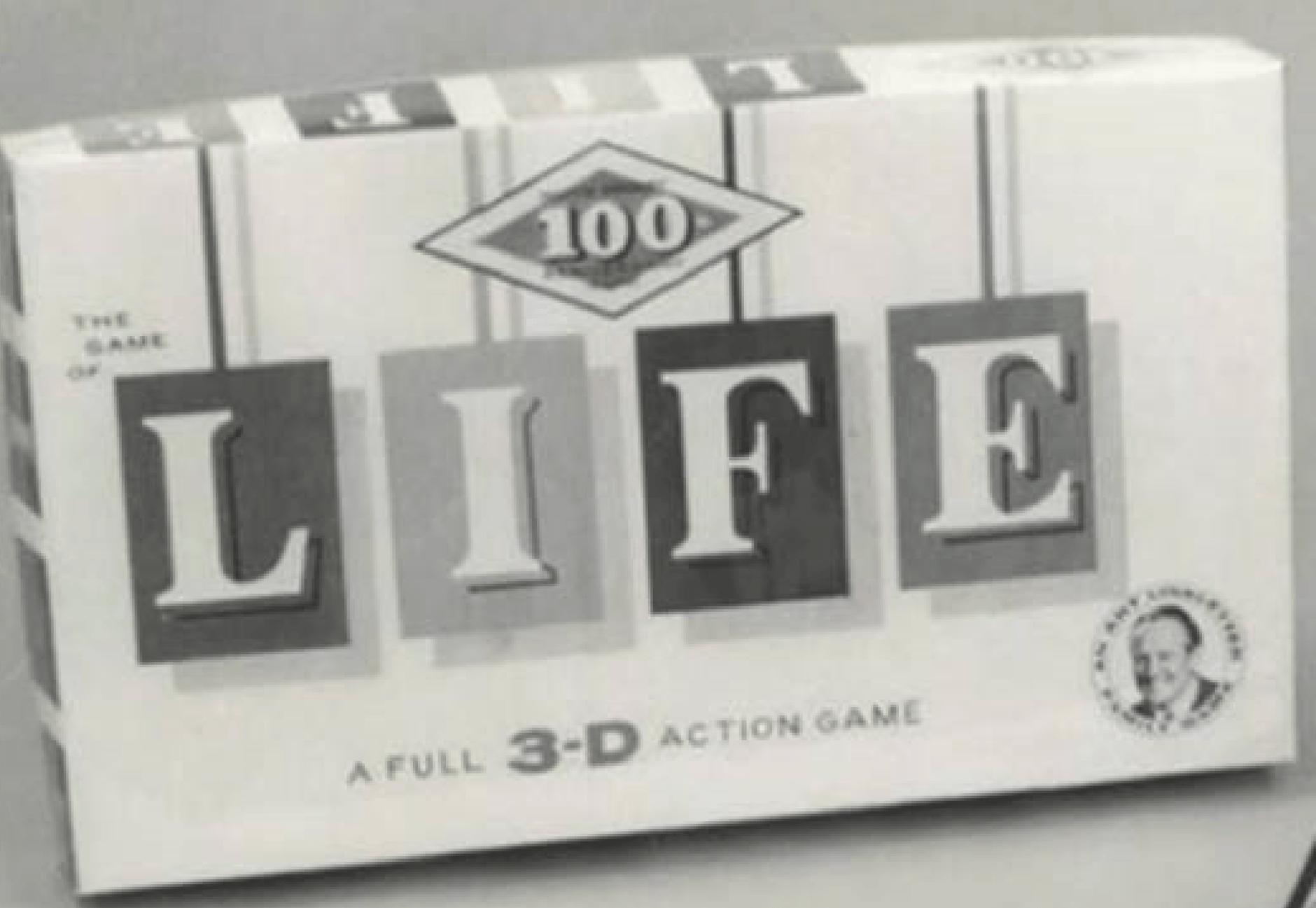

Known simply as “Life” today, American’s first parlor game was launched in 1860 by Milton Bradley when the future business magnate was a struggling lithographer. In 1959, as Bradley’s eponymous company approached its centennial, businessman Reuben Klamer asked designer Bill Markham to create a prototype update.

The modern game featured players riding around the board in a convertible, able to get married, have children, go to college or into business, buy stocks and insurance, and get rewarded for taking risks.

Hasbro would later buy the Milton Bradley Company in 1984, but Klamer’s deal brought in his business partner, Art Linkletter, a popular TV personality. Linkletter became the game’s spokesman, endorsing it on the back of the box and having his picture appear on the game’s $100,000 bills. Markham assigned his rights to a company controlled by Klamer and Linkletter.

The game went on to become one of the most popular of all time; it has been translated into 20 languages and is in the permanent collection of the Smithsonian. More recent versions have replaced the convertibles with minivans and allowed players to acquire pets and file lawsuits.

In 2015, Markham’s heirs sued to terminate his assignment, which is allowed under the 1976 Copyright Act as long as the product wasn’t a “work for hire.” But a Rhode Island federal judge found that the game was a work for hire because Klamer hired Markham to design it.

Alternatively, the judge said, it was a work for hire because Markham’s two employees, Grace Chambers and Leonard Israel, created much of the game under his direction.

Pollaro complained that the judge had allowed this alternative argument to be sprung on him at the last moment.

“We were told on the eve of trial, and I don’t mean the metaphorical eve of trial but literally the day before trial,” that the defense would be allowed to make this claim, Pollaro said.

“Were you able to depose Chambers and Israel after this defense came out?” asked U.S. Circuit Judge O. Rogeriee Thompson, an Obama appointee.

“Absolutely not!” Pollaro replied.

Thompson wanted to know if Chambers’ and Israel’s trial testimony was consistent with their depositions.

“Absolutely not!” Pollaro replied again. “At deposition they had no idea who actually created the physical prototype,” he said, but they testified differently at trial.

But U.S. Circuit Judge Kermit Lipez suggested that didn’t matter since the judge’s primary holding was that Klamer was the hirer.

Lipez, a Clinton appointee, was more interested in Markham’s assignment agreement, which he said “seems to acknowledge that Mr. Markham was the creator and inventor.”

“Theoretically that document would allow you to overcome the presumption that this was a work for hire,” Lipez observed. “I was somewhat troubled by the way in which the district court dismissed the significance of that.”

But Hasbro’s lawyer, Joshua Krumholz, said the language in the agreement “is a belt and suspenders provision” that merely provides that, “to the extent that” Markham had any rights, they’re included.

“That provision doesn’t vest Mr. Markham with any rights,” and he never applied for a copyright, said Krumholz, who practices with Holland & Knight in Boston.

Thompson was skeptical. “Does the assignment agreement say, ‘to the extent that,’ or does it just say he’s assigning his rights?” she asked.

Krumholz looked it up. It refers to rights “to which Markham may be entitled,” he answered.

U.S. Circuit Judge William Kayatta noted that the agreement stated that “Markham has invented, designed and developed” the game.

“That still doesn’t make him a copyright author,” Krumholz replied.

“I guess it doesn’t say ‘authored,’” acknowledged Kayatta, an Obama appointee.

Klamer’s lawyer, Patricia Glaser of Glaser Weil in Century City, California, argued that Klamer — and not any of the other parties — was the copyright holder because he supervised Chambers and Israel.

Kayatta was puzzled, asking, “What difference does it make” to the issue of whether the game was a work for hire?

Lipez added: “You’re asking us to resolve a dispute that’s not at the heart of this case.”

But both Glaser and Pollaro said it mattered because the case included a request for a declaratory judgment as to who held the copyright.

In any event, said Pollaro, Klamer stated in a 1989 lawsuit that he had no firsthand knowledge of anything Chambers and Israel were doing, so his contrary statements at trial shouldn’t be believed.

Klamer never sought an assignment from Chambers and Israel because he assumed that they were independent contractors, Pollaro asserted.

Kayatta was interested in the fact that Markham first laid the track on the board at a dinner with Linkletter and Milton Bradley executives at Chasen’s restaurant in Hollywood.

“It was a dramatic move at an expensive restaurant,” replied Krumholz. “But that’s not a physical creation. Assembling something is not a creative act.”

Subscribe to Closing Arguments

Sign up for new weekly newsletter Closing Arguments to get the latest about ongoing trials, major litigation and hot cases and rulings in courthouses around the U.S. and the world.