WASHINGTON (CN) — The Supreme Court on Thursday ruled that Andy Warhol’s Prince silkscreen series violated copyright laws.

The 7-2 ruling said Warhol's foundation violated a photographer's copyright when it used her photo in a work for a commemorative magazine honoring Prince.

“Lynn Goldsmith’s original works, like those of other photographers, are entitled to copyright protection, even against famous artists,” Justice Sonia Sotomayor wrote for the majority.

Justice Elena Kagan — with whom Chief Justice John Roberts joined — dissented from the ruling, claiming the court found marketing decisions should outweigh those of artistic expression.

“For in the majority’s view, copyright law’s first fair-use factor — addressing ‘the purpose and character’ of ‘the use made of a work’ — is uninterested in the distinctiveness and newness of Warhol’s portrait,” the Obama appointee wrote. “What matters under that factor, the majority says, is instead a marketing decision: In the majority’s view, Warhol’s licensing of the silkscreen to a magazine precludes fair use.”

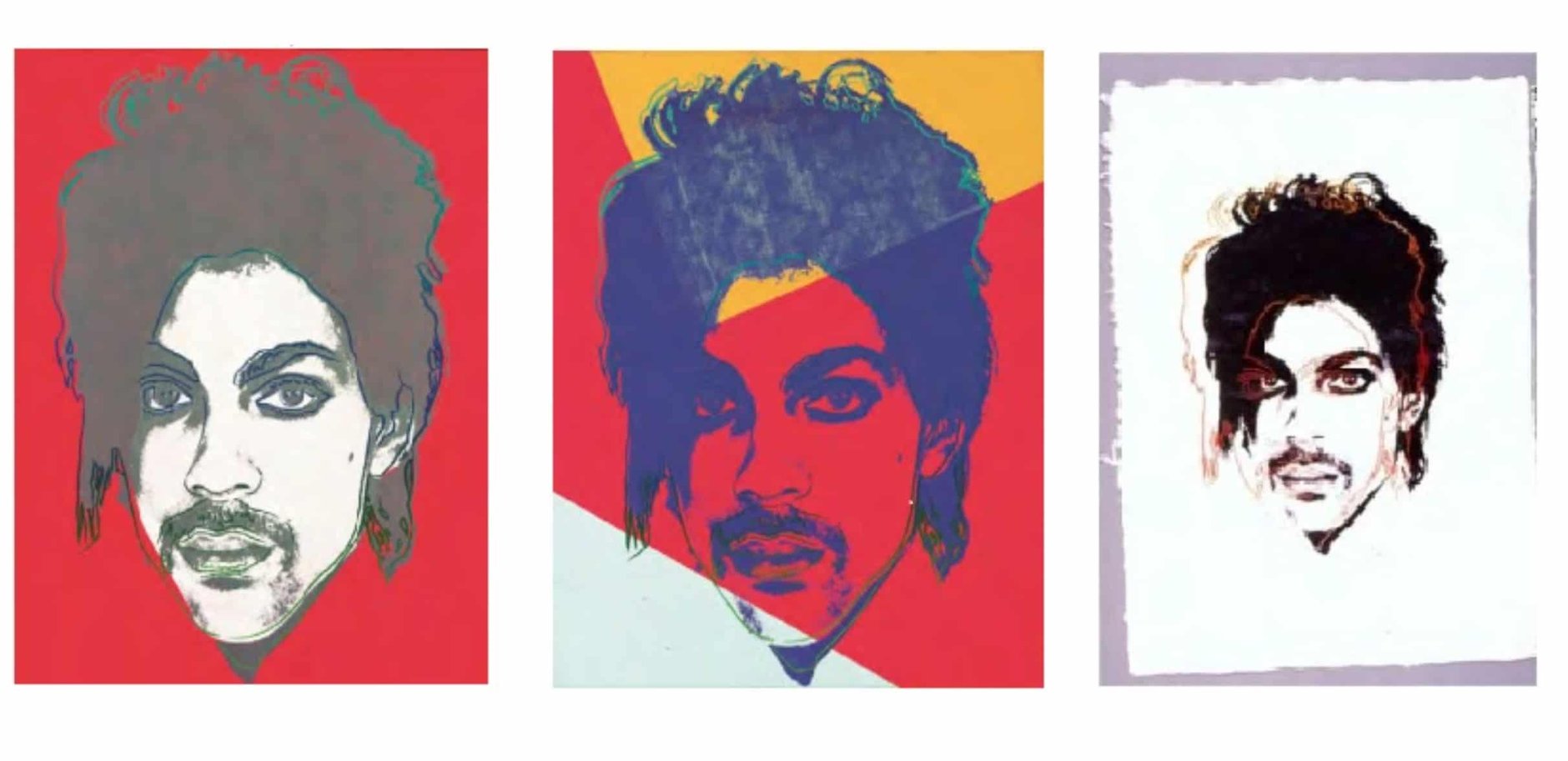

In the 1980s, Warhol was commissioned by Vanity Fair to create art of Prince for an article titled “Purple Fame” using a photo of the late musician taken by celebrity photographer Lynn Goldsmith. While Goldsmith had agreed to allow the magazine to use her work, Warhol took it a step further with his 12 silkscreen paintings that became known as the Prince series. The image featured in Vanity Fair’s 1984 issue was just the tip of the iceberg for the Prince series. In the years to come, Warhol’s collection would be displayed in museums, galleries, books, and other magazines.

The real conflict in this case came after Prince’s death in 2016. Vanity Fair reposted the 1984 “Purple Fame” article online, and Conde Nast created a commemorative magazine using the Prince series. Goldsmith claimed the Prince Series infringed on her copyright and contacted the Andy Warhol Foundation for compensation. In return, the foundation filed a declaratory judgment that the Prince series is protected as fair use.

Photographs like Goldsmith’s are protected by the Copyright Act. Creators get exclusive rights to reproduce, distribute, and display their own art, however, these rights are not without exceptions. Other creators can claim fair use, and use copyrighted art without infringing on an artist’s copyright. To do this, the follow-on works are evaluated for their purpose and the character of their use.

The question before the justices in this case centers around the qualifications for the fair use defense. According to Warhol, the Prince series was “transformative” from Goldsmith’s original work, changing its meaning and message, and, therefore, qualifies under fair use.

A federal judge agreed with Warhol, but the Second Circuit reversed setting up a high court battle.

While many of the justices shared their creative preferences during arguments in October, it wasn’t clear how they might rule on the case.

Sotomayor said the court’s only role in the dispute was to answer if the purpose and character of Warhol’s art should be considered “fair use” of Goldsmith’s photograph.

“The first fair use factor considers whether the use of a copyrighted work has a further purpose or different character, which is a matter of degree, and the degree of difference must be balanced against the commercial nature of the use,” Sotomayor wrote.

Sotomayor said Warhol’s Prince art in the commemorative magazine held substantially the same purpose as Goldsmith’s photo.

“Both are portraits of Prince used in magazines to illustrate stories about Prince,” Sotomayor wrote. “Such ‘environment[s]’ are not ‘distinct and different.’”

The majority also weighed the commercial use of Warhol’s Prince art, finding it was similar to Goldsmith’s because both were licensed to magazines.

“Taken together, these two elements — that Goldsmith’s photograph and AWF’s 2016 licensing of Orange Prince share substantially the same purpose, and that AWF’s use of Goldsmith’s photo was of a commercial nature — counsel against fair use, absent some other justification for copying,” Sotomayor wrote. “That is, although a use’s transformativeness may outweigh its commercial character, here, both elements point in the same direction.”

If the court had ruled against Goldsmith, Sotomayor contends, it would greenlight the commercial copying of photos.

“As long as the user somehow portrays the subject of the photograph differently, he could make modest alterations to the original, sell it to an outlet to accompany a story about the subject, and claim transformative use,” Sotomayor wrote.

Kagan claims the court took a novel posture in the case — a characteristic in law she finds less appealing than in art. She says the majority’s holding upends the evaluation required by the court’s precedents for copyright cases. Instead of looking at Warhol’s work, Kagan claims, the majority looked at the licensing agreement he entered into with the magazine.

“Because the artist had such a commercial purpose, all the creativity in the world could not save him,” Kagan wrote.

Goldsmith praised the court's ruling, saying it favored photographers and other artists.

"I am thrilled by today’s decision and thankful to the Supreme Court for hearing our side of the story," Goldsmith said in a statement provided by her attorney. "This is a great day for photographers and other artists who make a living by licensing their art. I want to thank the team at Williams & Connolly for sticking with me from the lows to this incredible high."

The Warhol Foundation said it disagreed with the ruling but was grateful for its narrowness.

“We respectfully disagree with the Court’s ruling that the 2016 licensing of Orange Prince was not protected by the fair use doctrine," Joel Wachs, president of The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, said in a statement. "At the same time, we welcome the Court’s clarification that its decision is limited to that single licensing and does not question the legality of Andy Warhol’s creation of the Prince Series in 1984."

The court’s ruling was seen as both narrow and broad by court watchers. The majority made clear it was only addressing the first fair use factor, however, changing the law in that area could still have major impacts.

“By focusing the first fair use factor on the purposes of the works at issue, and emphasizing the importance of whether a challenged use is commercial or non-commercial, the Court has rewritten an entire body of case law that had previously treated the focus of the first fair use factor as whether or not a challenged work was ‘transformative,’” Bruce Ewing, co-chair of Dorsey & Whitney’s intellectual property litigation practice group, said in a statement.

Subscribe to Closing Arguments

Sign up for new weekly newsletter Closing Arguments to get the latest about ongoing trials, major litigation and hot cases and rulings in courthouses around the U.S. and the world.