WASHINGTON (CN) — Art is in the eye of the beholder but its use thereafter will be decided by the Supreme Court this term.

On Wednesday the justices will hear arguments in Andy Warhol Foundation v. Goldsmith, a case that could decide how copyright laws interpret art created using other art.

Celebrity photographer Lynn Goldsmith photographed the late musician Prince in 1981. Those photos would then be repurposed by famed artist Andy Warhol three years later for a Vanity Fair article titled “Purple Fame.” The magazine commissioned Warhol to create art of Prince for the article and provided Goldsmith’s photo as a reference. Goldsmith had granted Vanity Fair the right to use the photograph as a reference for the issue.

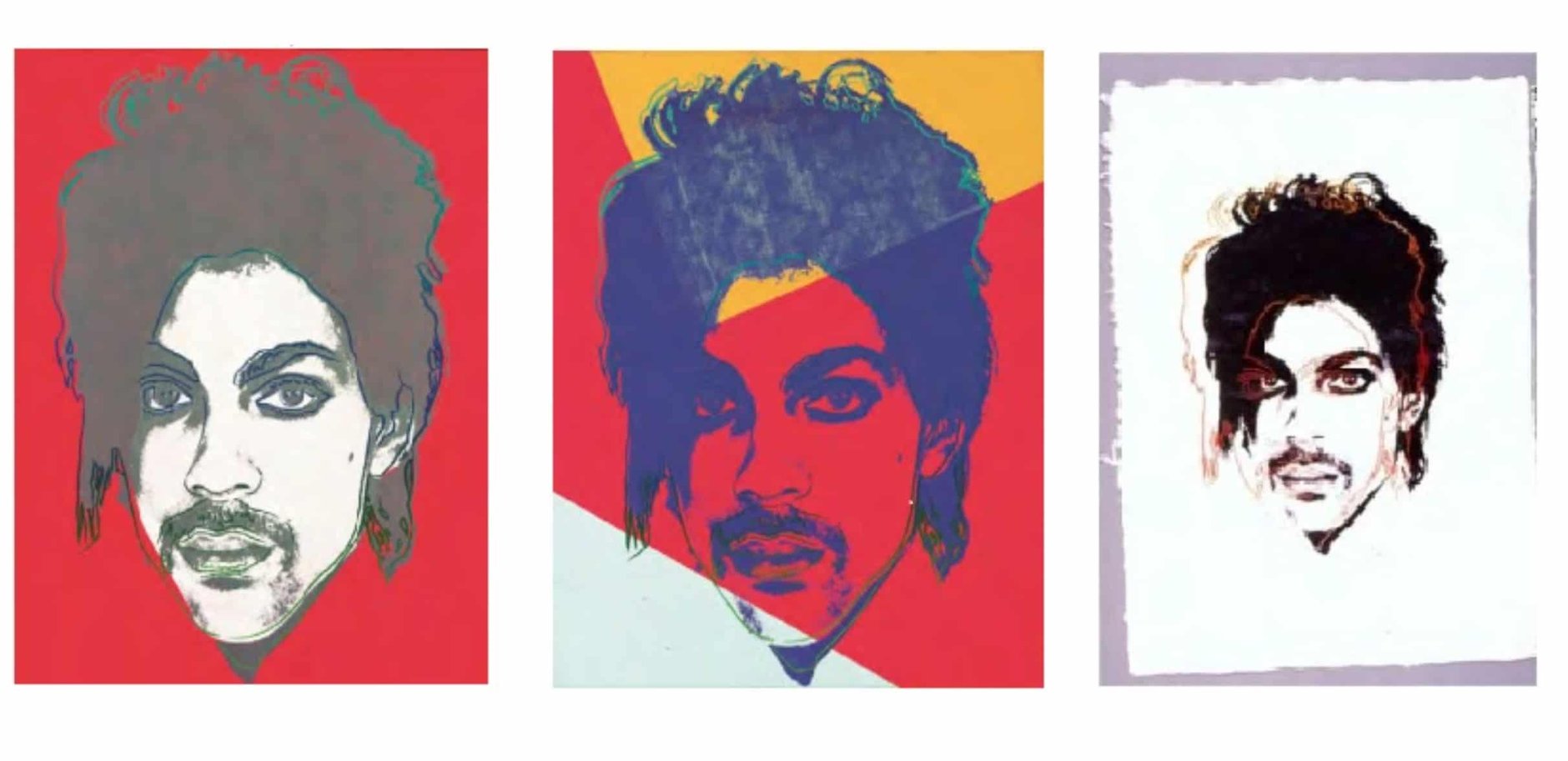

In the end, Warhol would create 12 silkscreen paintings — known as the Prince Series — using Goldsmith’s photo. The image was first cropped and resized, then altered with changes to the tones, lighting and detail. Warhol’s work also added layers of colors and outlines to accentuate some of Prince’s features.

One image from the series was published in the 1984 issue of Vanity Fair, but the collection would go on to be displayed in museums, galleries, books and magazines. Art collectors have paid top dollar for the prints, with a 2015 work going for over $170,000.

When Prince died in 2016, Vanity Fair reposted the 1984 “Purple Fame” article online. Conde Nast also used the Prince Series in a commemorative magazine. It was then that Goldsmith contacted the Andy Warhol Foundation, claiming the Prince Series infringed on her copyright. The foundation filed a declaratory judgment that none of the Prince Series used copyrightable elements and is protected as fair use. This led to counterclaims from Goldsmith for copyright infringement.

The Copyright Act protects original works of art and gives creators exclusive rights to reproduce, distribute or display their art. There is a fair use exception to these exclusive rights, however, that allows for the use of copyrighted art without the infringement on the copyright.

To qualify under the fair use defense, the follow-on work is evaluated for its purpose and the character of the use. This evaluation is what’s before the court: If the follow-on work conveys a different meaning or message from the original art, can it be considered “transformative” and therefore not infringe on the copyright.

A federal judge found that Warhol’s Prince Series was transformative, meeting the fair use defense, but the Second Circuit reversed.

Goldsmith argues that creators and the licensing industry rely on the promise of control over artists’ own work enshrined in the Copyright Act. She acknowledges that there are exceptions to the law, but this is not one of them. Goldsmith said if the court were to adopt the foundation’s approach to copyright law, there would be no law at all.

“AWF’s test would transform copyright law into all copying, no right,” Lisa Blatt, an attorney with Williams & Connolly representing Goldsmith, wrote in her brief. “Altering a song’s key to convey different emotions: presumptive fair use. Switching book endings so the bad guys win: ditto. Airbrushing photographs so the subject conforms to ideals of beauty: same. That alternative universe would decimate creators’ livelihoods. Massive licensing markets would be for suckers, and fair use becomes a license to steal.”

The foundation, on the other hand, argues that the court’s precedents support the meaning or message test. The foundation also claims that the fair use doctrine was intended to safeguard creativity.

“We think that making it harder for follow-on artists to borrow works in circumstances where they really are creating new art and adding a meaning or message that's different from the original, we think that that is extremely important to incentivize and protect artists to do that,” Roman Martinez, an attorney with Latham & Watkins representing the foundation, said at a recent Federalist Society event previewing the case.

A group of artists told the court that the Second Circuit’s ruling diverges from artistic tradition and creates risks for practicing artists. Not only would follow-on art become risky, but artists who use historical or political images would be in danger since only a few conglomerates own most of the market.

“The expanded risk of legal liability — or the threat of new lawsuits — would deter such artists from creating the works they wish to make, out of worry that those works may not appear visibly different enough to be considered transformative by certain judges,” Brian Willen, an attorney from Goodrich & Rosati representing the group, wrote in their brief. “This is particularly dangerous and worrisome to artists who do not have the financial resources to fight copyright litigation — which, practically speaking, means that this decision poses a threat to the vast majority of working artists in the United States.”

Artists are not the only parties who have weighed in on the case. Many big media names — like the Screen Actors Guild and Motion Picture Association — submitted amicus briefs in the case. The Screen Actors Guild favors Goldsmith’s arguments and asks the court to get rid of the meaning or message test. The Motion Picture Association meanwhile supports neither party.

“Andy Warhol’s use of respondent Goldsmith’s Prince photograph may or may not be the kind of commentary that qualifies as fair use under a proper application of the statutory criteria in the Copyright Act,” Donald Verrilli, an attorney with Munger Tolles representing the association, wrote in its brief. “But it cannot possibly be found to be fair use for the reasons advanced by petitioner.”

The association says Warhol’s argument represents an expansion of fair use in which any use adding meaning or message counts as transformative. They ask the court to scale back transformative use. The association claims that a ruling from this court that affirms the expanded definition means anyone could make an adaptation of a work without an artist's permission. For example, the sequel to a movie or spinoff films could be considered to “transform” the original work, and artists would be freely exploited for profit.

“If kept within proper bounds, the concept of ‘transformative use’ can play a helpful, indeed important, role in the fair use inquiry,” Verrilli wrote. “But loosed from those bounds, the ‘transformative use’ inquiry threatens to upend the proper functioning of copyright law.”

Subscribe to Closing Arguments

Sign up for new weekly newsletter Closing Arguments to get the latest about ongoing trials, major litigation and hot cases and rulings in courthouses around the U.S. and the world.