CHARLESTON, S.C. (CN) — It was a Saturday night at Solomon Ford's Place. Men lingered outside the raucous piccolo joint in Union Heights as Jake Varner quietly ducked inside.

The local laborer returned after a few moments, dressed in a yellow sport shirt and blue trousers with striped yellow socks. Old scars marred his arms, and a silver ring adorned his right hand.

Without word or warning, Varner pulled out an ice pick and stabbed another man twice in the chest and once more in the back. The victim told police he fled down the street to his vehicle.

“He kept following me and I got a gun out of the glove compartment,” the man said in a statement. “He turned around and I shot at him once. I didn’t know whether I hit him or not, but as I fired, he turned around and started back towards me and I shot again.”

The shooter was Republican presidential candidate Tim Scott’s grandfather, Artis Ware.

Varner died from gunshot wounds that night — Sept. 5, 1953.

Ware was charged with murder.

Ware looms large in Scott’s campaign narrative. The South Carolinian left grade school to pick cotton in the Jim Crow South, Scott has told crowds, but lived long enough to see his grandson become the first Black senator elected in the South in more than a century.

For Scott, the family’s ascent from “cotton to Congress” is proof of progress toward racial equality in the United States, even as the nation continues to reckon with the brutalities of slavery.

“Today, I am living proof that America is the land of opportunity and not a land of oppression,” he told supporters as he announced his presidential bid in North Charleston.

It’s difficult to parse the facts of a homicide after 70 years. Police misspelled the names of some witnesses in documents and recorded the wrong age for Ware. The accounts differ in the details, sometimes in important ways, and the case's resolution is ambiguous.

But the narrative belies the messy realities of Ware’s life. Using city directories, newspaper accounts and other historical materials, Courthouse News verified information in the court record to piece together details about a man who would inspire his grandson to pursue the nation's highest office.

A spokesman for Tim Scott's campaign declined to comment for this story.

Homicide at the neighborhood bar

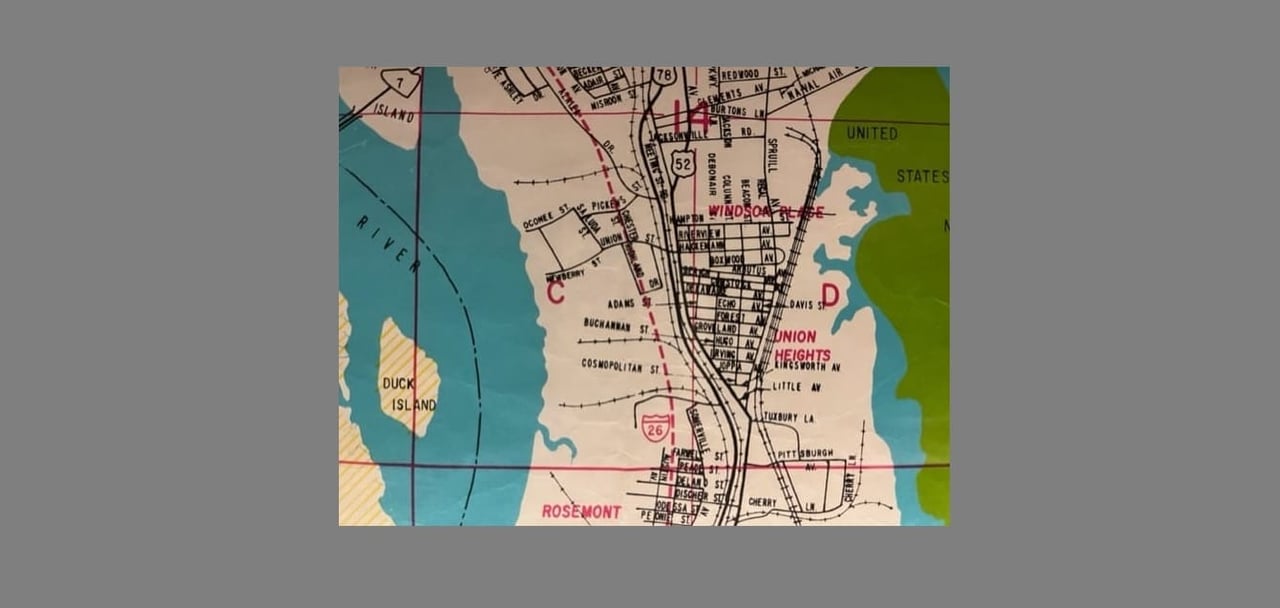

In 1953, Ware was a 32-year-old laborer living in the Daniel Jenkins Homes, a segregated federal housing project constructed 10 years earlier to accommodate the influx of shipyard workers who thronged Charleston during World War II. A Charleston city directory from 1950 shows he lived there with his wife, Louida, and their four children, including Scott’s mother, Frances.

The project was built on land leased from the Virginia-Carolina Chemical Company in “The Neck,” a skinny tongue of land that connects the Charleston peninsula to the mainland. The company’s fertilizer plant belched foul-smelling fumes that dirtied windows and dulled the paint on residents’ cars. Tests would later show lead and arsenic from phosphate mills contaminated the land.

Ware told police he went to Solomon Ford's Place for a dance the night of the shooting. The piccolo joint, or small bar, was about a mile east of the Jenkins Homes in Union Heights, a predominantly Black community founded after the Civil War by former slaves.

Ware went to the bar around 9:30 p.m. with his friend, Leo Fleming, he told police. He drank a beer and chatted on the street with several men before he spotted Varner, 30, enter the bar.

Two men, Moses Pringle and Burnie Witherspoon, witnessed the violence.