OMAHA, Neb. (AP) — President Donald Trump likes to joke that America's farmers have a nice problem on their hands: They're going to need bigger tractors to keep up with surging Chinese demand for their soybeans and other agricultural goods under a preliminary deal between the world's two largest economies.

But will they really?

From Beijing to America's farm belt, skeptics are questioning just how much China has actually committed to buy — and whether U.S. farmers would be able anytime soon to export goods there in the outsize quantities about which Trump has boasted.

It amounts to $40 billion a year, according to Trump's trade representative, Robert Lighthizer. If you ask the president himself, though, the total is actually "much more than'' $50 billion.

U.S. farm exports to China have never topped $26 billion in any one year.

What's more, since Trump's trade war with Beijing erupted last year, China has increased its farm purchases from Brazil, Argentina and other countries. As a result, Beijing may be locked into contracts it couldn't break even if it intended to increase its purchases of U.S. agricultural goods to something approximating $40 billion.

"History has never been even close to that level," said Chad Hart, an agricultural economist at Iowa State University. "There's no clear path to get us there in one year."

"The figure of $40 billion is larger than I expected," added Cui Fan, a trade specialist at the University of International Business and Economics in Beijing, "and I wonder whether the United States can ensure the full supply of the products."

U.S. farmers would surely like to. The farm belt has endured much of the impact from Beijing's retaliatory tariffs since July 2018, when Trump imposed taxes on $360 billion in Chinese imports. Beijing struck back by taxing $120 billion in U.S. exports, including soybeans and other farm goods that are vital to many of Trump's rural supporters.

The impact from China's retaliatory tariffs was substantial: U.S. farm exports to China, which hit a record $25.9 billion in 2012, plummeted last year to $9.1 billion. Soybean exports to China fell even more — to a 12-year low of $3.1 billion, according to the Department of Agriculture. Farm imports to China have rebounded somewhat this year but remain well below pre-trade-war levels.

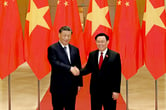

The so-called Phase 1 deal that the two sides announced Dec. 13 did manage to de-escalate the standoff and offer at least a respite to U.S. farmers. Yet the truce put off the toughest and most complex issue at the heart of the trade war: The Trump administration's assertion that Beijing cheats in its drive to achieve global supremacy in advanced technologies such as driverless cars and artificial intelligence.

The administration alleges — and independent analysts generally agree — that China steals technology, forces foreign companies to reveal trade secrets, unfairly subsidizes its own firms and throws up bureaucratic hurdles for foreign rivals.

Beijing rejects the accusations and claims that the United States is trying to suppress a rising competitor in international trade.

Under the preliminary U.S.-China deal, Trump suspended his plan to impose new tariffs and reduced some taxes on Chinese imports. In return, Lighthizer said, China agreed to buy $40 billion a year in U.S. farm exports over two years, among other things. Beijing also committed to ending its longstanding practice of pressuring foreign companies to hand over their technology as a condition of gaining access to the Chinese market.