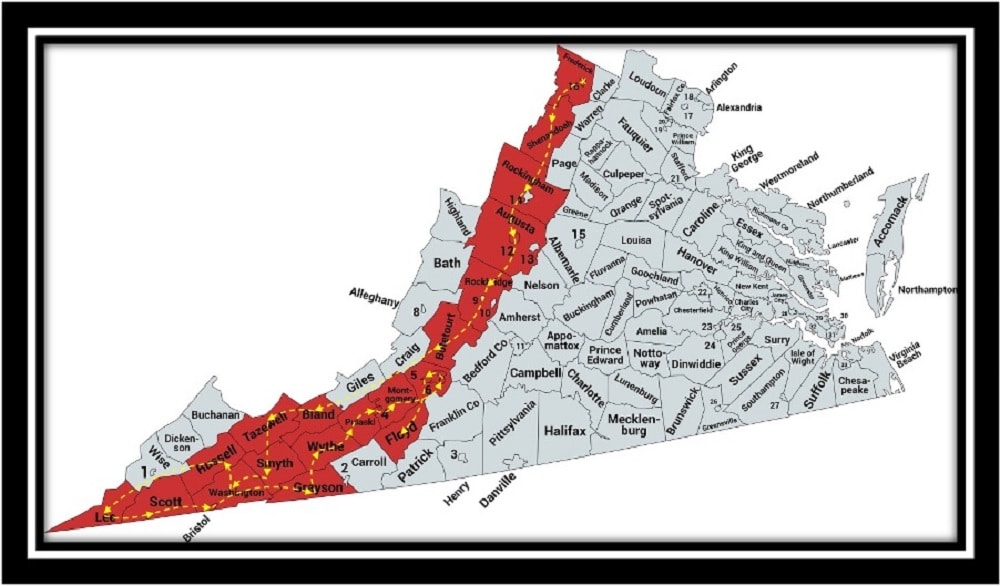

Traveling more than 1,000 miles over the course of five days, Courthouse News journalists visited 25 Virginia circuit courts to report on civil complaints filed in those courthouses. Their goal was to demonstrate what it would take to cover the public record of the Virginia courts by visiting each courthouse in person.

The trip took the journalists down the western edge of the Commonwealth and into the small counties of southwest Virginia. During five days from September 19 through September 23, 2022, they started when one clerk’s office opened and finished their work late in the afternoon as the last clerk’s office closed.

In all those 25 courts, the journalists printed a total of 10 recent complaints that were sufficiently newsworthy to include in Courthouse News new litigation reports, out of hundreds of lesser matters.

During their travels, they also found a network of working clerks who wanted to give reporters online access but said they could not. Nearly all the clerks freely gave public access to a “vault” that contained paper land records and often civil case records, while also serving as a historical library for the court. Within the vaults were computer terminals that displayed an icon that says “CPS,” standing for Circuit Public Search, a program developed and maintained by the Richmond-based Office of the Executive Secretary, often referred to as OES. The records seen through the Circuit Public Search program were the same records that can be seen online through a program called Officer of the Court Remote Access, or OCRA, also developed and maintained by the Executive Secretary.

The journalists discovered that the local clerks were caught in a web of payments to the Executive Secretary, contracts with the Executive Secretary, and rules made by the Executive Secretary. All of which prevented the clerks from allowing the journalists to sign up for online access. The Executive Secretary’s dominance of access was so pervasive that one clerk compared the Executive Secretary’s software to the Wizard of Oz because it controlled “everything.”

As Mid-Atlantic Bureau Chief Ryan Abbott, Northeast Bureau Chief Adam Angione and California-based Editor Bill Girdner traveled from one court to the next, word spread and the journalists were expected by clerks who said, “I heard.” It emerged that the clerks and officials from the Executive Secretary’s office had been having active online discussions about the journey of the journalists and their request to subscribe for online access. While the full content of the discussion was not known, the results were evident: the clerks were convinced they did not have authority to grant journalists access to OCRA.

A typical exchange took place in Roanoke City Circuit Court where the three Courthouse News journalists approached the clerk’s counter and were quickly directed to a waiting area around the corner from the office of Clerk Brenda Hamilton. They sat down in a row in seats along the wall and she soon came striding around the corner.

“Are you officers of the court!” she demanded.

They answered in rough unison that they were not, they were journalists.

“I can’t give it to y’all, she said. “Sorry Harry. Too big a weight to carry!” She said Supreme Court rules prevented her from giving online access to journalists.

Another telling exchange took place in Salem City Circuit Court where Clerk Chance Crawford listened carefully to their request for access online. “I’m not saying I totally disagree with you,” he said, measuring his words. “I can’t allow it unless we get something from the federal court with regards to your lawsuit that it’s OK.”

Frederick County Circuit Court, Winchester City Circuit Court

The 25-court trip started in Frederick County, the northernmost county of Virginia, where both the city and county courts are located in the same building. Both clerks gave access to civil records on a local terminal and both denied access online.

At the counter in Winchester City Circuit Court, a deputy clerk named Anne showed the reporters behind the counter into the records area. She gave Abbott, whose bureau includes Virginia, a form to sign up for OCRA but added, “It’s for attorneys. I don’t know what you do as reporters.”

Abbott printed out one complaint and paid a copy fee of 50 cents per page. Around 521 civil cases had been filed in the current year in the county court, and 429 in the city court. On the way out of town, the three journalists stopped by the historic home of Patsy Cline whose songs were played and sung throughout the Angione household as he grew up in Ohio.

Shenandoah County Circuit Court

The journalists drove south on Virginia State Route 628 past several wineries and over Turkey Run Creek until they arrived at the courthouse in Woodstock. They were buzzed into a large, open area filled with land records. County Clerk Sarona Irvin said OCRA is only for attorneys. She referred to “liability” and “the Legislature” as reasons for refusing online access. “I would rather you had online access,” she added. “It’s more convenient."

Abbott printed out two newsworthy complaints from the Circuit Public Search program on a local terminal. The court had received 970 new civil case so far in 2022. Three women offered free Bible lessons on the sidewalk in front of the courthouse. The journalists had lunch at the Woodstock Café across the street.

Rockingham County Circuit Court

They drove south on winding roads toward the Blue Ridge Mountains and halted to see the 7 million-year-old rock formations of the Luray Caverns, including the “Dream Lake” reflecting pool. They then continued south, crisscrossing the Shenandoah River before heading west on Route 33 into Harrisonburg where Rockingham County Circuit Court is located.

A form provided by a deputy clerk specified that the applicant must be either a Virginia attorney or working directly under same. Abbott printed one complaint out from the public search terminal in the vault and paid the copy fee. The court has seen 2,204 civil cases filed in 2022.

Augusta County Circuit Court

The journalists continued ever south on routes 253 and 11 through the manicured campus of James Madison University and past the imposing barracks of the Augusta Military Academy before arriving at the Augusta County Clerk’s Office in Staunton. Deputy Clerk Gina Coffey said “the code” would not allow her to sign journalists up to OCRA. She said a bar number is required but noted that only a business license is needed for online access to Secure Remote Access which holds marriage records, deeds, financial reports and judgments.

While searching the Circuit Public Search program on a local terminal, Abbott pointed out that docket information, which is available to the public online, describes many complaints simply as “catch-all” complaints and also imposes a character limit on party information such that clerks often omit some party names. From the terminal, where case numbers had reached 1,854 so far in 2022, Abbott printed one recent complaint. The cashier took his payment.

On the counter next to her was a stack of fliers about a local ballot measure to decide whether the new courthouse should be built in the current courthouse location or in nearby Verona. Asked by Abbott which she thought best, the cashier pointed to the Verona option, saying, “Cheaper.”

Staunton City Court

The journalists were promptly told by a deputy clerk that OCRA is only for attorneys. The civil case numbers had reached 455. The clerk’s office was closing as they left, and they stopped in Staunton for the night. They had dinner at the Mill Street Grill where they were served by a waitress named Shea, after the stadium, who was monitoring the Mets game on a phone in her jean pocket, while working.

Rockbridge County Circuit Court

Tuesday morning, the journalists drove south on Route 252 through a rolling terrain of green hills, old wood barns and prosperous farms of the Shenandoah Valley. After an hour, they arrived at Rockbridge County Circuit Court where a group of clerks concluded, “Only attorneys can have access to OCRA.” But they gave Abbott an application form anyway. Abbott printed out one complaint. Civil case numbers had reached 566 for the year.

Botetourt County Circuit Court

The journalists drove south along Broad Creek and crossed the James River, then continued on Highway 220 toward Fincastle, where they arrived at Botetourt County Circuit Court. “Only attorneys,” said the counter clerk in answer to their question. They were then buzzed into the vault which, as in almost all the courthouses, doubled as a historical library. Alongside the public terminal, a long rifle owned by a man born in 1805 was mounted on the wall, and on a shelf was a book about Virginia courthouses.

Abbott printed out one complaint and paid for it at the counter. The civil case numbers had reached 400. They had lunch at the Pie Shoppe across the street.

Bland County Circuit Court

From Fincastle, they drove southwest on forested roads through the New River Valley where leaves were turning to yellow and orange, past Coal Bank Hollow Road and Dismal Falls, to arrive two hours later at Bland County Circuit Court.

A deputy clerk named Lesa Berry let them into the records room, where Abbott checked the recent civil cases through a public terminal. “It’s a public record,” said Berry, referring to the civil complaints. She added, “Most people come in to check deeds and land records.” Berry texted the clerk to ask about OCRA access for journalists, then returned to tell them, “The site would have to approve it.”

Civil case numbers had reached 235 for the year.

Tazewell County Circuit Court

The journalists crossed the Appalachian Trail on North Scenic Highway and then headed west hugging Wolf Creek, before taking Route 61 south to arrive at Tazewell County Circuit Court.

At the counter a clerk told Abbott online access to OCRA is only for attorneys. Posted next to her was a notice saying fines can now be paid online. In the vault, Abbott checked the public search program on the local terminal where case numbers had reached 1,035 for the year.

Now deep into Southwest Virginia, the journalists drove up the switchbacks of the Back of the Dragon. The narrow and winding road went through dense forest and emerged to overlooks on a vast green valley with occasional farms. They reached Marion after Smyth County Circuit Court had closed and spent the night.

Smyth County Circuit Court

Wednesday morning, shortly after the court opened, the journalists arrived at the courthouse and were directed into the vault where terminals provided local access to civil records. On the wall was a framed photo of the Smyth County Bar Association in 1985. There were 19 lawyers in the photo, 18 men and 1 woman.

Referring to OCRA, Clerk John Graham noted, “It’s a subscription service so it’s not on the internet.” Nevertheless, he said, “the code” prevented him from granting press access online. The case numbers had reached 789 for the year.

Washington County Circuit Court

The journalists took Lee Highway south to Abingdon where Clerk Patricia Moore told them that most local lawyers still file their papers in the narrow lobby, adding, “Some days, you can’t swing a dead cat around here without hitting an attorney.”

She explained the wide-ranging role of the clerks in a county she described as “hillbilly adjacent.” During the pandemic, she was called to attest to the marriage of elderly constituents as they lay on their death beds, to help the transition of an estate to a common-law spouse.

She was also asked to pull deeds and drop them off for constituents, and occasionally acted as a “de facto probate judge.” The clerk was also creating a set of TikTok videos titled “Did You Know,” aimed at the people of Washington County, telling them how to file their documents and handle juror duties. But she would not let the journalists subscribe. “OCRA is only available to attorneys,” she said. “The Supreme Court has not offered it to the public. It’s just for officers of the court.”

She added that she had heard ahead of time what the journalists were looking for. She said she would love to take their subscription fee as her budget is so tight that she had to go to Costco and pay for the blue tape that marked the floor during the pandemic, showing where filers should stand. Abbott printed two complaints and paid the fee. Civil case numbers had reached 1,433 for the year.

Russell County Circuit Court

Turning north, the reporters drove Route 19 through Hansonville and Willis until they arrived at Russell County Circuit Court. They made their way past the stately façade of the courthouse and went around the corner to a small, non-descript doorway off the back parking lot. It was 12:03 by then, and the uniformed officers at the entrance said the clerk’s office was closed for lunch.

Later contacted by bureau chief Abbott, Clerk Ann McReynolds said, “Only attorneys and probation officers and people like that can sign up for OCRA.” Asked why that was, she said, “Because that’s how it’s always been since it started.” Abbott pointed out that the clerk in Alexandria Circuit Court allows journalists to subscribe for online access to civil case records, McReynolds simply repeated, “OCRA is just for attorneys.”

Lee County Circuit Court

The journalists drove west on U.S. Highway 58, as the houses and farms grew smaller and the Baptist churches grew more frequent, to arrive at Lee County Circuit Court.

Clerk Rene Lamey invited them into her office. She had been working in the clerk’s office in Lee County at the furthest west end of Virginia for over 20 years. “Lee County is where Virginia starts,” she said. “So we try to set a high bar.”

She described herself as a working clerk, not an administrator, while her phone rang, her watch buzzed, an iPad lay in a silver case on her desk, a cellphone played a pop song as it rang, and her computer screen was open to an ongoing discussion, in addition to which a uniformed officer came in needing a signature.

She painted a dismal picture of her court’s finances and consulted her budget to confirm that she pays the Executive Secretary an annual software maintenance fee of $3,900 plus annual payments for hardware and software of $11,000. OCRA subscriptions bring in $100 per subscriber but she has only 11 paying subscribers. Her limit on the number of subscriber slots is 35 and she is required to ask the Executive Secretary to increase her allotment if she needs more.

She tentatively agreed to allow Abbott to sign up for OCRA online. But the subscriber interface — controlled by the Executive Secretary — requires the subscriber to certify he or she is a member of the Virginia bar or a government official, in order to proceed to a review of court records. Abbott was neither and could not make the certification. Therefore he could not review civil circuit court records for Lee County online.

Abbott and Angione checked the public search program on the local terminal in the clerk’s vault where Clerk Lamey had assembled an old hand stamp and other courthouse artifacts in a small historical display. Case numbers had reached 215 so far in 2022.

Scott County Circuit Court

Forty-five minutes east on Highway 58, over the Clinch River and down Daniel Boone Road, the journalists arrived at the courthouse in Gate City. They were allowed into the public records vault and could use the Circuit Public Search program from there. But the deputy clerk at the counter said “only attorneys” can sign up for online access to OCRA. The clerk himself, Beau Taylor, was not in his office that day. But he later talked with Abbott and said, “Look, if the judge says I’m not breaking the law I’d be the first in the state to sign y’all up."

Civil case numbers had reached 616 for the year. The journalists finished the day driving another 30 miles east to Bristol, where they stayed the night in a hotel on the Virginia side of State Street but had dinner on the Tennessee side.

Bristol City Circuit Court

“I heard,” said Clerk Kelly Flannagan in the Bristol City court on Thursday morning when asked if she already knew the purpose of the journalists’ visit. She said the civil complaints are “public records” and noted that she has a good relationship with the local press.

Flannagan confirmed that the docketing software provided by the Executive Secretary limits the number of characters when typing in the parties. She also confirmed that, like other Commonwealth clerks, she creates bar numbers for officials who are not attorneys, so they can use OCRA online. The clerk said her budget is so tight that if the wood table behind her broke, she would have to put it back together with super glue.

Nevertheless she refused to take their offer to pay the subscription fee for OCRA access. “Reporters are not officers of the court. Until that language is changed, I follow the rules.” Asked what remedy the journalists had, she referred them to the Office of the Executive Secretary, saying, “Contact OES to figure it out.”

Abbott printed out one complaint. The case numbers for the year stood at 544.

Grayson County Circuit Court

Taking Interstate 81 north to Chilhowie, then south on Route 762, past Little Granny’s Lane, and east on Highway 58, they arrived at Grayson County Circuit Court which sits atop a hill in the town of Independence.

A deputy clerk said, “OCRA is only for attorneys,” and said the clerk herself was in court. The vault, open to the public, contained an expansive collection of public records. The search program on the local terminal showed case numbers had reached 144 for the year.

In a courtroom up one floor, Clerk Susan Herrington was sitting at the bench to one side of the judge considering the case against a man stopped in his truck carrying a 9mm handgun and a blue pipe containing crystal methedrine. The judge sentenced him to one year’s probation.

Wythe County Circuit Court

Going north on Highway 21, the journalists drove past Cripple Creek and arrived at Wythe County Circuit Court where Clerk Jeremiah “Mo” Musser got up from his desk as the journalists walked in. A big man in a loose blue suit and tie, he said online access to OCRA is restricted. “It’s officers of the court. Probation has it, Commonwealth attorneys have it.”

“Why won’t they let you have it?” he added. Musser went back to his office to find the amount charged by OES to run the OCRA software. “Twenty nine hundred!” he said in a loud voice when he came back.

Describing the Executive Secretary’s software, he said, “It’s like the Wizard of Oz. It controls everything.”

Musser described himself as “working clerk” and not an “administrator” like the clerks in the Eastern Virginia courts, such as Chesapeake City Circuit Court, who "mostly handle HR.” Before the journalists left, he regaled them with stories of his run for the clerkship. He pointed to the spot behind his knee where he was hit and knocked down by a billy goat. He described the sound of a rooster — “like a helicopter” — attacking his head before he fought it off with his cowboy hat. He roughly pantomimed being mooned through a glass door at a drug-using house by a very large man. All that, he said, was while seeking permission to plant campaign signs. The owner of the rooster, he said, watched it all from his second floor window and told him he wished he had a video. “He told me to come on back and I could put up a sign.”

The case numbers in Mo’s court had reached 859 for the year.

Pulaski County Circuit Court

A half-hour east on the Lee Highway took the journalists down into Draper's Valley and past Calfee Park, home of the Appalachian League’s Pulaski River Turtles, to the circuit court. A deputy clerk named Terri Hagen told the journalists she had heard they were traveling in the region.

She said she could not let them subscribe to OCRA online. “You have to have a bar number,” she said. “The programs we bought were set up for officers of the court so they don’t have to come into court.” The yearly rate for online OCRA access is $200 per year, she said, adding, “We have a lot of subscribers.”

The journalists checked the Circuit Public Search program on a local terminal in the clerk’s vault. Case numbers stood at 464 for the year.

Radford City Circuit Court

From Pulaski Town, it was a short drive northeast on Route 11 to Radford City Circuit Court, where a counter clerk said OCRA access online is only for attorneys. The public search program on the local terminal in the vault showed that case numbers had reached 184 for the year.

Montgomery County Circuit Court

Continuing northeast on the same route, the reporters arrived in Christiansburg where they entered a big, modern courthouse. “Only attorneys can sign up for it,” said the intake clerk at the counter.

In addition to public search terminals, the clerk’s extensive vault held paper case records going back to 1792. An attendant buzzed the journalists into a small side room that held particularly significant documents, including a census from the early 1800s that recorded the number of free men and women and slave men and women in each Virginia county. Case numbers seen on the search terminal had reached 1561 for the year.

The journalists then drove on to Blacksburg to attend a football game between the Virginia Tech Hokies and the West Virginia Mountaineers. The reporters found themselves walking to the stadium alongside the Virginia Tech Corps of Cadets as they called cadence, including, “With that bayonet in my hand, I want to be a stabbin’ man,” all the way into the game. Virginia Tech committed a number of mistakes and penalties and lost the game 33-10.

Past midnight, the journalists arrived at the Liberty Trust Hotel, a refurbished bank in Roanoke, and spent the night.

Roanoke City Circuit Court

Friday morning, shortly after the clerk’s office opened in Roanoke City Circuit Court — housed in a well-appointed structure betraying the affluence of the region — the journalists arrived and asked at the counter about subscribing for online access to OCRA. They were promptly directed to seats along the wall next to Clerk Brenda Hamilton’s office, just past a sign marked “Public Vault.” They sat all in a row and waited.

Hamilton soon strode around the corner and demanded, “Are you officers of the court!” More or less in unison they answered that no, they were journalists. “I can’t give it to y’all. Sorry Harry. Too much weight to carry!” Hamilton continued, “Can’t do it. Sorry. That’s the Supreme Court rules. It’s all set up there in the Supreme Court.”

She agreed that she pays a fee for the OCRA software but did not have the amount at hand. “Nothing in life is free,” she said. “Not even from the Supreme Court.” She told the journalists that they can request documents that her office will send them. “You can have anything you want.” But the reporters must call first, then send a check, and then wait for the requested document to be mailed back.

In the public vault, a terminal showed civil case numbers had reached 1840 for the year. Roanoke is a town of small shops and boutiques and is clearly in the midst of an economic resurgence. The journalists stopped for breakfast at Bread Craft, a small bakery that makes remarkably faithful artisanal French baguettes which they consumed with butter and black coffee.

Roanoke County Circuit Court

The journalists drove west on city streets to Salem where the Roanoke County Circuit Court is located. A Virginia Tech pennant hung high on a central pillar in the clerk’s office. “You’d have to have a bar number. It’s for attorneys,” said Deputy Clerk Jill Camilletti. She conceded probation and parole officers also have access. “They fall into the group that’s OK.”

She said her office’s online access to civil records costs $120 and the service has at least 50 subscribers. She pays the Executive Secretary roughly $35,000 per year, she estimated, for software maintenance and for hardware. When her office has difficulties with the software, she deals with a team from the Executive Secretary’s office. She said the teams are broken up by the software programs. “Different teams have responsibilities.” Case numbers had reached 1,150.

Salem City Circuit Court

Walking the short distance to Salem City Circuit Court, the journalists were ushered into Clerk Chance Crawford’s office. “I was waiting on ya,” he said with a wry smile. He said the clerks’ intranet carried news of their journey.

In answer to their request for online access, Clerk Crawford said, “Not yet.” And as they discussed the right of public access to court records, he said, “I’m not saying I totally disagree with you. I can’t allow it unless we get something from the federal court with regards to your lawsuit that it’s OK.”

After a wide-ranging and friendly conversation that included the politics of the region, the resurgence of Roanoke, and an analysis of the previous night’s Virginia Tech game, the journalists left for their 25th and final court. Case numbers in Salem City had reached 290 for the year.

Floyd County Circuit Court

They traveled south on Route 221 along a winding mountain road through Poages Mill and Copper Hill, stopping only to take on fuel, before they arrived at the Floyd County Courthouse. “I’ve heard why you’re coming,” said Clerk Rhonda Vaughn, getting up from her desk behind the counter in the small clerk’s office. “OCRA we provide to officers of the court. That’s the name of the program. That’s how we set up our agreements.” She said about 9 local attorneys and other officials were signed up for online access to civil records. As to why reporters could not sign up, she said, “It’s policy.”

The journalists then checked the vault of public records which, like almost all the rest of the courts they visited, was open to the public. Through a terminal in the vault, Abbott went to the Circuit Public Search site and checked for recent civil complaints but found none that were newsworthy. As they were on their way out, the clerk commented about the online access, “It’s very little used. I look at the usage, at the log-ins, and they don’t use it much.” New civil case numbers had reached 99.

Asked about the region, she said Floyd County is now home to a number of musicians and is becoming an artist destination. With that, the reporters said she could inform the rest of the clerks communicating through their intranet site that the press visits had come to an end. They waved and said, “We’re outta here.”

The road home

The three journalists departed after visiting their 25th court on a five-day voyage from the north to the south along the western side of the Virginia Commonwealth. The odometer on their red rental Toyota had started at 25,373 and now stood at 26,409, representing travel of 1,036 miles. They had found 10 new civil cases for their reports on new and noteworthy litigation. It was a little after 2:00 on Friday afternoon and they were headed to Charlotte for flights home to Washington, New York and Los Angeles.

This report, available as a PDF here, was prepared by Mid-Atlantic Bureau Chief Ryan Abbott, Northeast Bureau Chief Adam Angione and Editor Bill Girdner.

Subscribe to Closing Arguments

Sign up for new weekly newsletter Closing Arguments to get the latest about ongoing trials, major litigation and hot cases and rulings in courthouses around the U.S. and the world.