BOSTON (CN) — A trio of judges showed little indication of their leanings Monday while asking wide-ranging questions about the impact of a $10 billion lawsuit by the Mexican government accusing U.S. gunmakers of encouraging illegal weapons trafficking to gangs and cartels.

Mexico fought to revive its claims against seven U.S. gun makers — including Smith & Wesson, Beretta, Colt, Glock and Ruger — which it deems responsible for 340,000 guns being smuggled across the southern border each year, leading to as many as 17,000 murders per year and economic damages of almost 2% of the Mexico’s GDP.

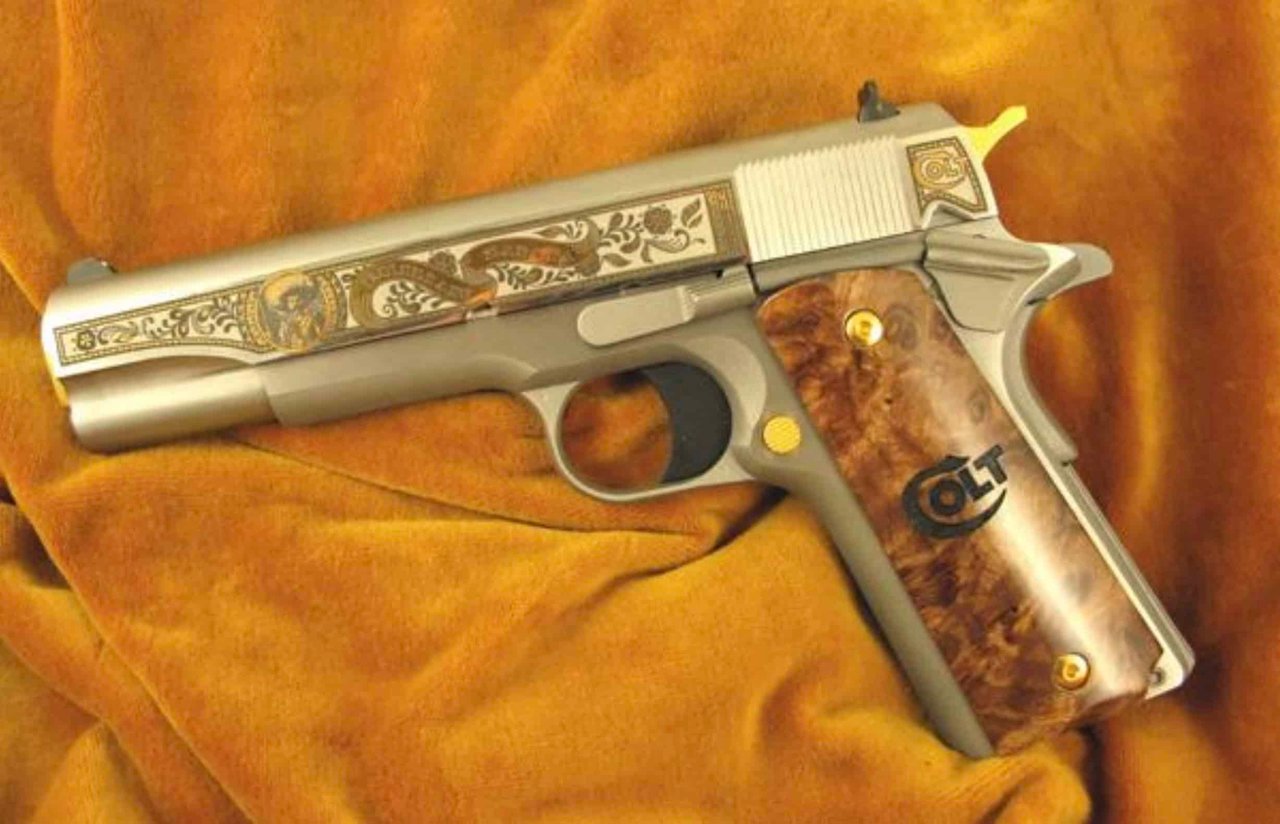

In its complaint the Mexican government says the gunmakers score $170 million in annual sales by illegally selling their weapons to corrupt dealers who they know will traffic the guns to gangs and cartels. Colt even manufactures three .38 caliber pistols specifically tailored to the Mexican market that are prized by criminal gang members: the “El Jefe,” the “El Grito” and the “Emiliano Zapata 1911.”

On behalf of Mexico, attorney Steve Shadowen of Hilliard Shadowen in Austin, Texas, argued that federal laws don’t apply outside the United States unless Congress explicitly says so.

“Again and again and vociferously,” has the Supreme Court made this clear, Shadowen argued. “[If] applying a law has some foreign policy implication, that decision has to be made by the political branches and not the courts.”

Mexico has extremely strict gun laws: The entire country has a single gun store, located on a military base, and it issues fewer than 50 gun permits a year. By contrast, there are roughly 20,000 gun stores in the four U.S. states that border Mexico.

Bridging the border, the case could touch on legal far-ranging questions like the Second Amendment, routine criminal cases and Russian interference in the U.S. economy, lawyers said Monday at the First Circuit Court of Appeals.

If the lawsuit is allowed, “Mexicans would have greater rights than U.S. citizens,” U.S. Circuit Judge Gustavo Gelpí said.

“Yes, and that’s not an unusual circumstance,” Shadowen offered.

The gunmakers’ attorney, Noel Francisco of Jones Day in Washington, D.C., argued that a ruling for Mexico would allow China and Russia to wreak havoc by enacting their own laws in order to file disruptive lawsuits in U.S. courts. He also warned that such a ruling would have “dramatic implications to all defendants charged with aiding and abetting throughout this country” and “push the bounds of aiding and abetting well beyond where it’s ever gone.”

Thirteen states and the District of Columbia filed an amicus brief supporting the claim against the gunmakers.

A lower court threw out the suit last September, finding it was barred by the Protection of Lawful Commerce in Arms Act, a 2005 federal law that bars most lawsuits against gun makers for criminals’ misuse of guns. The act has an exception for suits alleging that a violation of a statute proximately caused an injury.

When Shadowen suggested ceding some of his time to co-counsel Jonathan Lowy to discuss the details of the exception, U.S. Circuit Judge William Kayatta approved: “Good idea.”

Lowy, president the group Global Action on Gun Violence, argued that the gun makers deliberately make products that can easily be modified into illegal machine guns and that those products therefore qualify as illegal machine guns under federal law. He also argued that the manufacturers are aiding and abetting illegal trafficking because they know that some of their dealers are corrupt.

“If someone goes into a gun store and says ‘I want a dozen assault weapons and thousands of rounds of ammunition,’ you know they’re a trafficker,” Lowy said. “We have one case where someone walked in and bought 85 assault weapons.”

Francisco insisted that a gun doesn’t become illegal just because it’s easily modifiable to make it illegal. If that were true, he said, “you’ve converted millions of Americans who possess AR-15s into criminals.”

Much of the argument amounted to a polite duel between Francisco, who served as U.S. solicitor general under President Donald Trump, and Kayatta, an Obama appointee.

Francisco argued that even if the gun makers knew they were selling to weapons traffickers, that wasn’t aiding and abetting unless they treated the corrupt dealers differently from the legitimate dealers. He cited a unanimous Supreme Court decision in May holding that Google, Facebook and Twitter weren’t responsible for aiding and abetting terrorist attacks even if they knew that their algorithms were pushing content to terrorists that could inspire violence.

Here, Francisco said, “everyone was licensed and all purchasers were legal.” And even if some of the dealers were corrupt, “there’s not a shred of evidence” that the gun makers themselves broke the law.

Lowy argued that the Twitter case “doesn’t help them at all. With regulated products sought after by criminals, like guns or drugs, the analysis is different. It’s not like tweets.”

In response to Gelpí’s repeated questions about the Second Amendment, Francisco argued that a ruling for Mexico would have “potentially crippling effects on ability of lawful purchasers to buy firearms.”

Kayatta compared this case to drug companies’ liability for selling opioids to pharmacists, but Francisco said the chain of causation was much more complicated here. “This case is a poster child for the essence of proximate cause,” he said.

Gelpí is a Biden appointee, as is U.S. Circuit Judge Lara Montecalvo, who rounded out the panel.

Subscribe to Closing Arguments

Sign up for new weekly newsletter Closing Arguments to get the latest about ongoing trials, major litigation and hot cases and rulings in courthouses around the U.S. and the world.