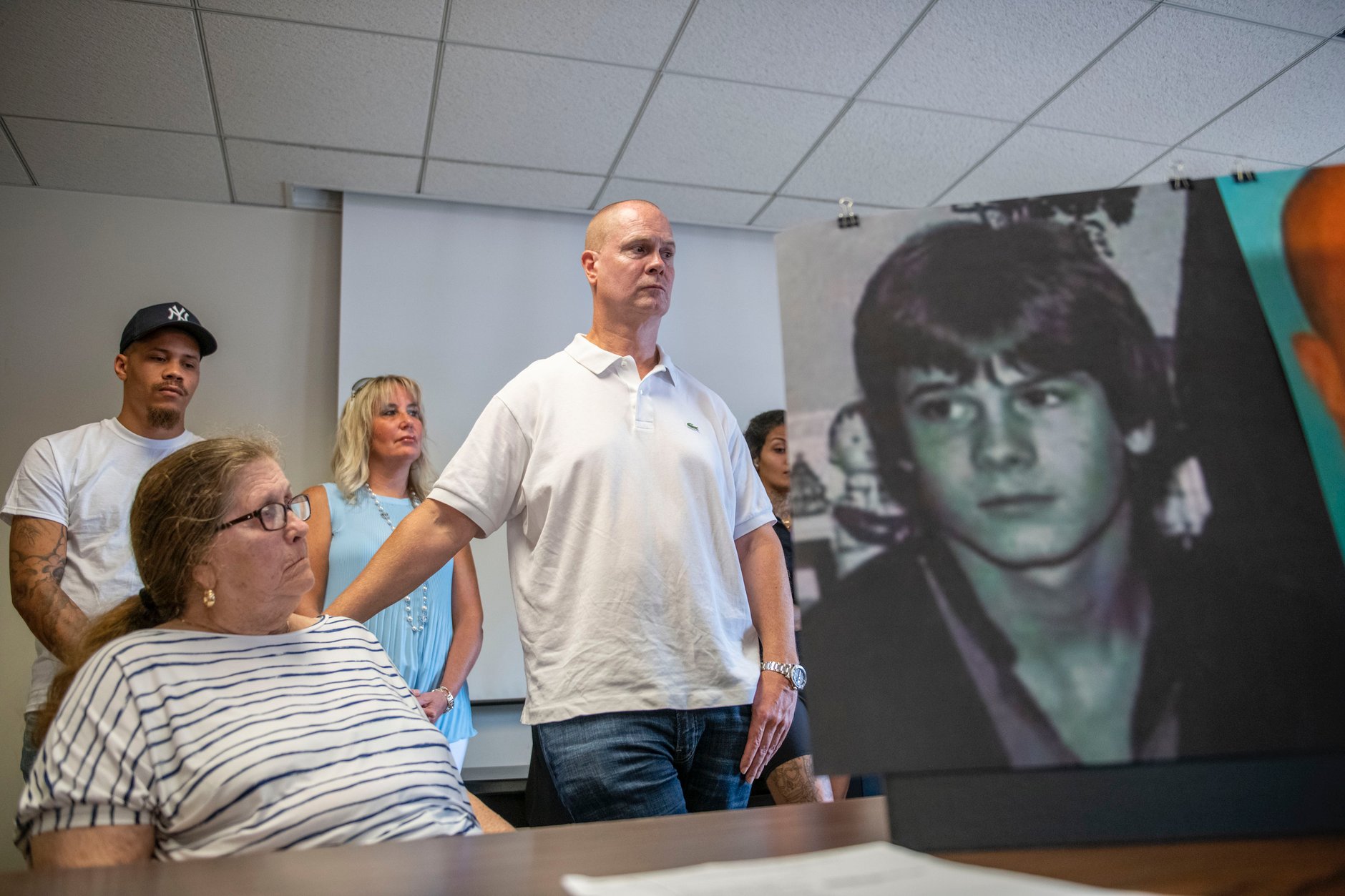

(CN) — A Detroit man employed by the FBI as an underaged drug informant in the mid-1980s filed suit against the federal government Friday, claiming state and federal law enforcement abandoned him to be attacked and arrested at 17, talked him into informing again throughout the 1990s, and went back on promises of immunity again once that investigation was complete.

Richard Wershe, Jr., dubbed “White Boy Rick” by news media and a 2018 Matthew McConaughey film loosely fictionalizing his life, alleges that FBI agent Jim Dixon recruited him at age 14 after his sister started dating a drug dealer and his father called the FBI.

This early recruitment, attorney Nabih Ayad wrote in the federal lawsuit, started a chain of events that led to the teenager narrowly escaping multiple murder attempts, being pistol-whipped by Detroit police and ultimately spending over 30 years in prison despite assurances of immunity.

After the teenaged Wershe was able to identify several individuals Dixon asked about, the agent and other members of a joint task force with the Detroit Police Department began picking him up unannounced, writing in the force’s files that their information came from the boy’s father.

Wershe was convicted for possession of a controlled substance in 1987 and sentenced to life without parole. He was 17 at the time and had become a “rising star” in Detroit’s drug trade at the task force’s direction, using task force money, the complaint states. Fearful of being discovered as the driving force behind a juvenile drug lord with rising public visibility, Wershe says the task force members stopped contacting their child soldier.

Between that abandonment and his arrest, drive-by shootings had hit his father’s house, nearly striking his father, and a car in which he was a passenger, though he escaped uninjured. He’d also been shot in the abdomen at point-blank range while still working with the FBI, an incident task force members led by FBI agent Herman Groman dismissed as an “accident” and told Wershe to cover up to increase his street cred.

An affidavit attached to Wershe’s complaint shed more light on that incident.

“Looking back, it is hard for me to believe that I believed them that they would keep me safe, but I did because I was a child and only because I was a child,” Wershe wrote.

“After I was shot, Groman, [DPD Officer Billy] Jasper, and [DPD Officer Kevin] Greene all came to my hospital bed and told me that I needed to say that the shooting was just an accident, that we had just been ‘playing’ when I got shot. They said that would be ‘better for everyone,’” he continued. “I see now they meant themselves.”

Wershe’s arrest followed a severe beating by Detroit police officers, which the complaint said had been spurred by growing media coverage of the “kingpin” known as White Boy Rick – a moniker Wershe said he’d never used for himself.

At the time of his release in 2020, Wershe was Michigan’s longest-serving prisoner convicted as a juvenile for a nonhomicide offense. He is also widely cited as the FBI’s youngest-ever informant, though the classified nature of such work makes that difficult or impossible to confirm.

In 1991, Wershe was offered another way out of prison when the FBI offered to put him in the witness protection program to work on Operation Backbone, a corruption investigation into then-Detroit Mayor Coleman Young, the city’s police department and their connections to the city’s drug underworld. His former FBI handlers, the complaint says, promised to go “balls to the wall” in their efforts to get him released from prison if he cooperated.

In his affidavit, Wershe said that he agreed to join Backbone “only because I wanted out of prison so badly and I believed [Groman and then-Assistant U.S. Attorney Lynn Hellend] when they said they would keep their end of the agreement.”

Once again, however, Wershe’s trust in the feds was not rewarded; the U.S. Attorney’s Office recommended against his release, which Hellend allegedly told him was retaliation by higher-ups at the office for informing against Detroit police officers. To make matters worse, Wershe alleged, his sealed testimony was released to the Michigan Parole Board and to the Detroit Police Department during his parole hearings, despite assurances from Hellend and other assistant U.S. attorneys that it would remain sealed.

Wershe’s release, some 32 years after his original arrest, came only after former FBI agent Gregory Schwartz admitted the agency's bait-and-switch treatment of Wershe to a parole board in 2012 and journalists and advocates brought more publicity to the child informant's case in 2017.

Neither the FBI nor Ayad’s office responded to requests for comment early Friday evening.

Wershe’s federal complaint was filed in the Eastern District of Michigan, where he now lives and works in the legal marijuana industry.

Subscribe to Closing Arguments

Sign up for new weekly newsletter Closing Arguments to get the latest about ongoing trials, major litigation and hot cases and rulings in courthouses around the U.S. and the world.