MANHATTAN (CN) - How — and where — should victims collect reparations for a genocide? In New York, an effort to hold present-day Germany responsible for what is grimly called the first genocide of the 20th century hit a setback.

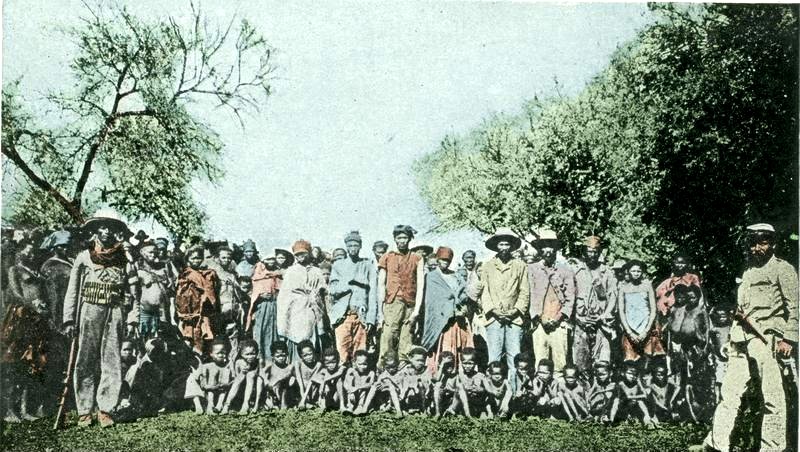

The case was brought by indigenous Ovaherero and Nama and descendants of the estimated 100,000 people who were systematically killed by colonizing Germans between 1904 and 1908 in what is now Namibia.

Ruben Carranza, senior expert on reparations for the International Center for Transitional Justice, noted that U.S. courts have become a resource for survivors of dictatorships, war criminals and genocides.

“Victims can of course file cases in their own countries’ courts – but those courts cannot reach assets in the U.S. or elsewhere and will not have the kind of political impact that a judgment in a country in which judges have a relative degree of independence and enforcement power can exercise,” Carranza said in an email.

In the United States, however, such cases face a high bar. After U.S. District Judge Laura Taylor Swain threw out Ovaherero and Nama’s suit earlier this month for lack of jurisdiction, attorney Ken McCallion appealed immediately, confident that the Second Circuit will give his clients a reversal.

Lead plaintiff Veraa Katuuo said that he and fellow litigants always knew they were in for a long haul.

“This is a unique and historical case, and through this process we succeeded to educate the world about the Ovaherero and Nama genocide at the hands of German soldiers, and in the process put brakes on the so-called government-to-government genocide and reparation negotiations,” said Katuuo, who founded the Association of the Ovaherero Genocide in the USA.

“We are going to take advantage of every avenue available to us within the United States judicial system, and hold ‘mighty’ Germany accountable for the crimes they have committed against the Nama and Ovaherero peoples,” Katuuo added in an email.

Several experts contacted about the case called it important for German society and government to do right by the Ovaherero and Nama, particularly given how the West has grappled for decades with fallout from the Holocaust. The latest version of Katuuo's complaint calls Germany’s annihilation efforts in southwest Africa a “precursor” to the events of World War II less than four decades later.

Carranza suggested a multipronged effort for reparations.

“There is no ‘best way,’” Carranza said. “Rather, there is the possibility of enlisting domestic (in this case, German) support from political leaders and German citizens in order to put pressure on a more justice-oriented German government to legislate reparations.”

William Darity Jr., an economist and professor of public policy at Duke University, also said German citizens should pressure their government to pass legislation for Ovaherero and Nama reparations.

“Trying to do this through the U.S. court system evades the question of who has direct responsibility and obligation for the compensation,” Darity said in an interview, wryly noting this same court system has a history of shooting down cases for domestic slavery reparations.

As alleged in Katuuo’s amended complaint, filed in February 2018, German settlers started moving to southwest Africa toward the end of the 19th century under the expansionist, white-supremacist concept of Lebensraum, or “living space.”

The presence of the well-established Ovaherero and Nama people, already sovereign nations on the territory, meant the German settlers had to rent land and sign treaties. Quickly breaking those treaties, German colonists seized 50,000 square miles of indigenous land plus livestock without compensation, according to the amended complaint. They raped indigenous women and girls, and enslaved others for manual labor.

Angered by this violent encroachment, the Ovaherero and Nama attacked in 1904 and 1905; a January strike by the Ovaherero killed 123 people. The Germans struck back, with devastating military support from the mainland. They called in Lt. Gen. Lothar von Trotha, who issued what is widely understood as a vernichtungsbefehl, or extermination order.