MEXICO CITY (CN) — As the world gears up to watch NASA’s return to the moon with the first launch of the Artemis program next week, Mexico is moving forward with its mission to put robots on the lunar surface later this year.

The Artemis program aims to put astronauts back on the moon by 2025, the next giant step in space exploration on humanity’s way to Mars. The Colmena (Hive) program is Mexico’s way of getting in on the action.

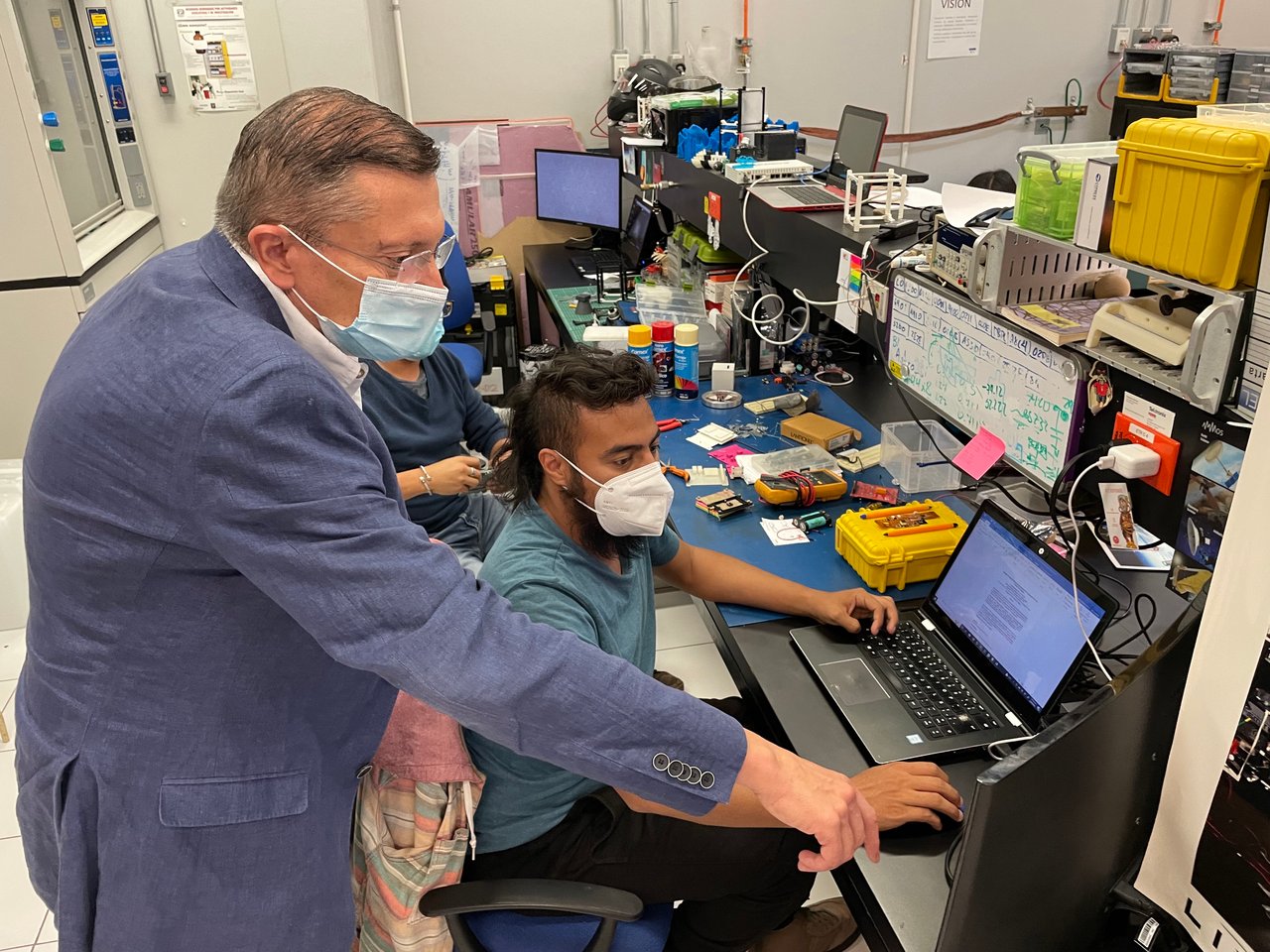

“This window will only be open a few short years,” said Gustavo Medina Tanco, head of LINX — the laboratory at Mexico’s National Autonomous University that designed the Colmena robots.

“If we don’t take measures to do this now, we’ll unfortunately end up consumers of the new services that come out of this next stage of space exploration, rather than producers,” he said.

Medina described the current landscape of space exploration and exploitation in terms that Earthlings who experienced the digital revolution of the Internet can easily understand. Mexico wants to get its foot in the door before the Googles and Facebooks of space exploration gobble everything up.

“Those who arrive first arrive small, but right away they grow exponentially into giants and then close the door behind them,” he said. “That’s what’s going to happen in space.”

Colmena consists of five tiny, two-wheeled robots weighing just two ounces and measuring less than five inches in diameter. These will be set into an innovative catapult device aboard a commercial lander named Peregrine, operated by the Pittsburg-based lunar logistics company Astrobotic.

The robots’ scientific mission is to study the features and composition of lunar regolith, the moon’s soil. This presented the first of several unique challenges to Medina and his team.

Lunar regolith ranges from visible dust grains to particles measuring mere nanometers across, and the ultraviolet rays from the sun charge this dust with electrostatic energy, creating a cloud of plasma that floats up to around a foot off the lunar surface.

“When we put rovers or astronauts on the moon, all this is at their wheels or their feet, but our little robots are only two centimeters tall,” said Medina. “This means that they live in this cloud of regolith, a completely different environment. No one has done this before, and this changes everything.”

Thus, his team could not simply take a big robot and make it smaller. They had to completely rethink the technology they planned to send, designing systems that would not be damaged by this “almost liquid” cloud of regolith.

However, the real challenge was figuring out how to do this on a shoestring. The Mexican Space Agency does not have the astronomical budget of a program like NASA, but by designing the robots for one specific purpose, they were able to save a lot of money compared to traditional space exploration materials.

“Lower costs allow you to completely change your work philosophy and run risks,” said Medina. “So instead of making things hurricane-proof, I’m going to certify things only for the exact purpose I want them to perform. I’m going to use this component that is for use on Earth, and if it fails, my costs were a thousand or a hundred times less, and I’ll just make another one, and it’ll still be much cheaper. It allows you to totally change how you think and act.”

For Medina’s students, seeing their tiny robots scurry through the lunar regolith will be the culmination of a series of exciting achievements.