WASHINGTON (CN) — The privately owned submersible that imploded deep beneath the Atlantic Ocean has raised questions about whether the company operating the vessel — and its founder who lost his life in the disaster — could have done more to ensure its safety.

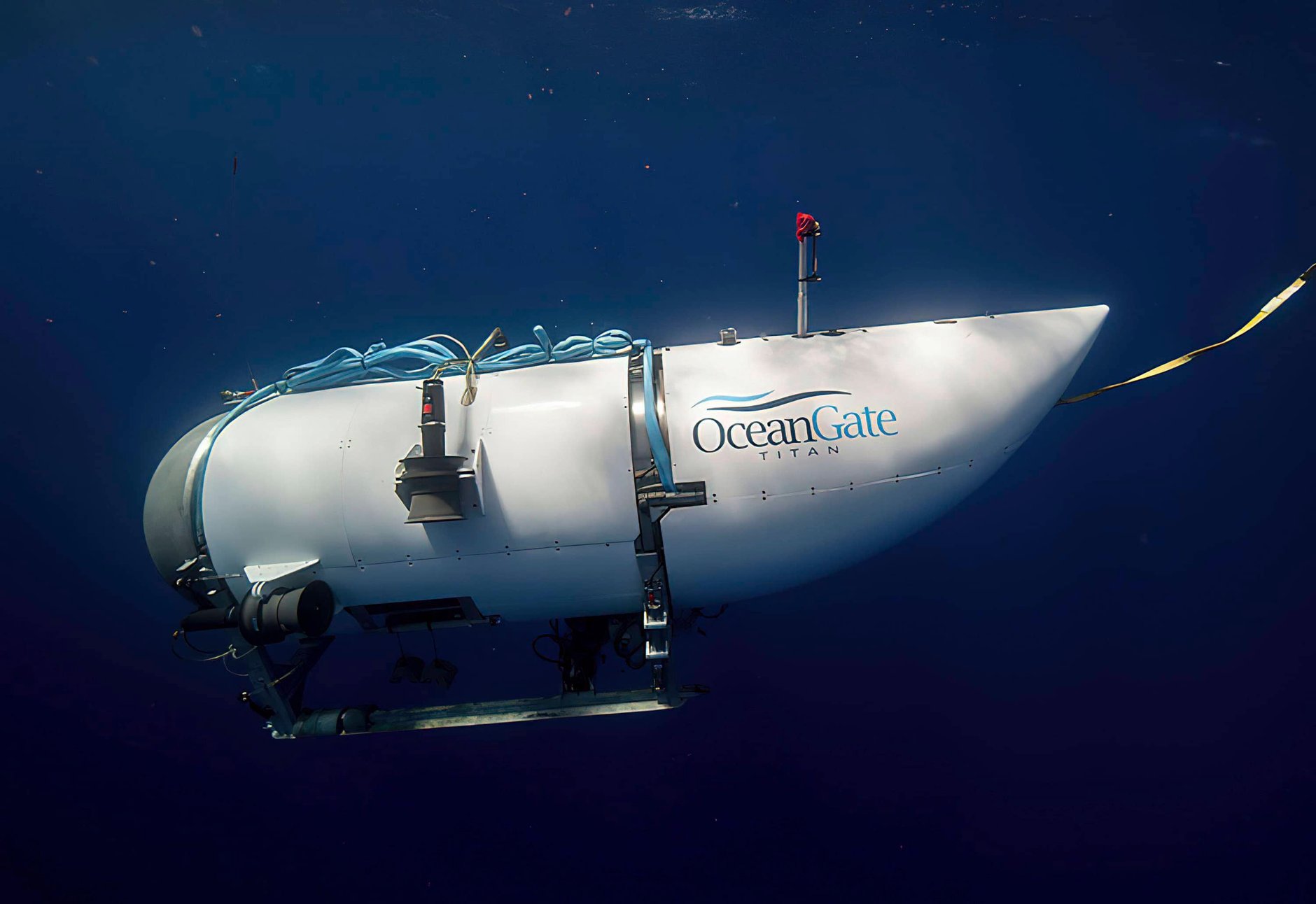

During a June 18 expedition to the Titanic wreck site, Washington-based expeditions company OceanGate lost contact with its Titan submersible, which was ferrying five passengers more than two miles below sea level to the sunken ship remains. Over the next few days, what began as a search-and-rescue mission for the missing vessel became a recovery operation, once it was revealed that Titan had imploded near the wreck site, presumably killing all on board — including OceanGate founder and CEO Stockton Rush.

The Coast Guard announced this week that it is investigating the circumstances of Titan’s disappearance.

Some experts have argued that Rush and OceanGate dangerously sidestepped safety provisions by allowing the Titan submersible to sail. What remains unanswered is whether the company violated any law — and whether United States lawmakers can act to prevent a similar disaster in the future.

After the submersible disappeared earlier this month, a 2019 op-ed by Rush resurfaced, in which the millionaire businessman said that the experimental craft would not receive a formal safety classification from an independent maritime organization, a common practice for companies operating charter vessels.

Rush argued at the time that getting an inspection from an independent organization such as the American Bureau of Shipping or Lloyd’s Register would stifle Titan’s innovative submersible design, which featured a carbon fiber hull and electronic monitoring systems.

“While classing agencies are willing to pursue the certification of new and innovative designs and ideas, they often have a multi-year approval cycle due to a lack of pre-existing standards,” Rush wrote. “Bringing an outside entity up to speed on every innovation before it is put into real-world testing is anathema to rapid innovation.”

Classing assessments also do not ensure a vessel is completely safe, Rush argued, claiming that the vast majority of marine accidents “are the result of operator error, not mechanical failure.”

Although Rush’s op-ed framed safety classification as a damper on Titan’s innovative design, some experts say OceanGate was only able to avoid such an inspection by exploiting grey areas in international law.

“I think it’s a classic case of dodgy regulation,” said Thomas Schoenbaum, a maritime law professor at the University of Washington School of Law, “and it points to a larger problem in that this so-called marine adventure tourism is becoming a big business.”

Under the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, vessels registered to a particular country must abide by international maritime regulations. Known as flag states, these countries provide government oversight to ships that sail under their colors, which could include safety inspections or classification.

Titan however did not sail under a national flag, Schoenbaum said, allowing OceanGate to bypass any sort of outside inspection.

“If you want to call it a loophole, it kind of is,” said Andrew Norris, an assistant professor of international law at the U.S. Naval War College and a former Coast Guard attorney. “It’s a loophole in international law.”

Vessels without a flag state are subject to the laws of the nation whose coastal waters they operate in, Norris explained: “If this vessel was carrying passengers for hire in waters subject to U.S. jurisdiction, we would have the right to step in.”

On international waters, however, the rules are different.

“If [Titan] didn’t have a flag state, then you’ve lost one of the main pillars under international law for ensuring the safe design, construction and ultimately certification of the vessel: the government,” Norris said. “If it had applied to fly under the flag of any country, that country at a minimum would have to ensure that it met whatever international standards exist, and it is almost always free to impose more design and construction standards that the thing would have to comply with.”