BUENOS AIRES, Argentina (CN) — The Falkland Islands (called the Malvinas in Spanish) lie 300 miles off the east coast of Argentina, which has long claimed sovereignty over the islands despite being a British overseas territory.

In 1982, a chain of disputes between Argentine and British authorities led to military ships from both countries being concentrated around the islands, which have a population of around 3,200 people.

At that time, Argentina faced a major economic crisis and growing civil unrest over the state-led terror campaign carried out by the military junta that led to the forced disappearance of 30,000 people. Internally, the junta was also dealing with struggles between the army and navy.

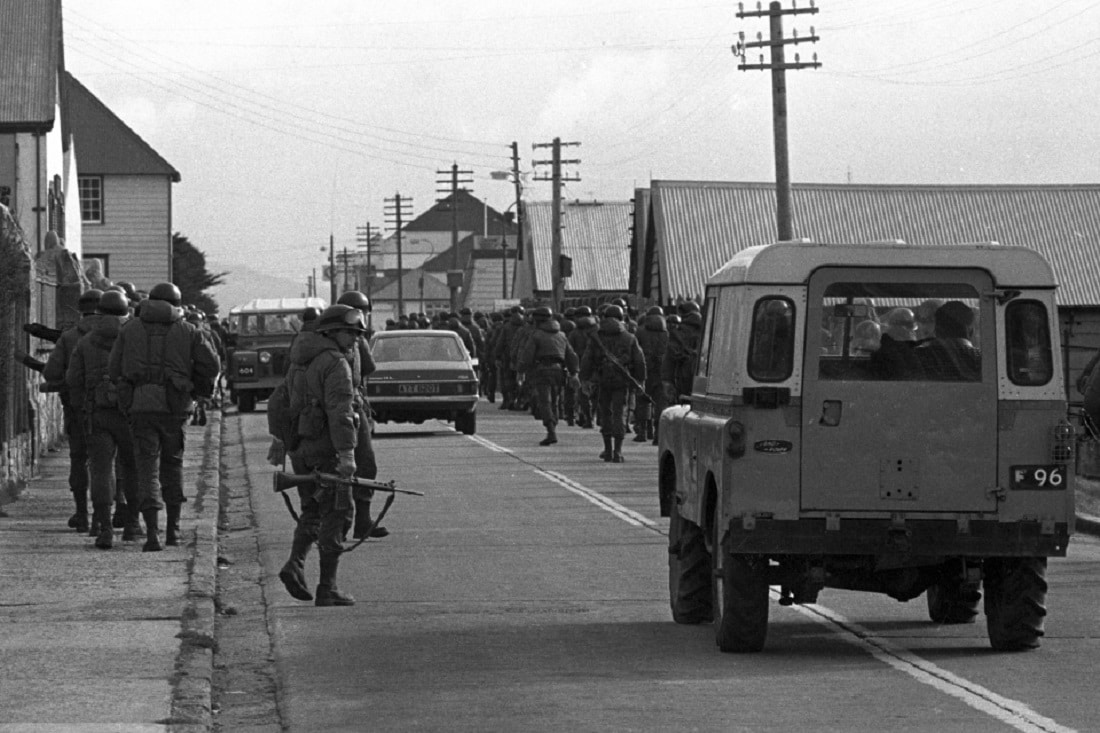

In an attempt to unify both the junta and the country around a popular national cause, then-President Leopoldo Galtieri abandoned forceful diplomacy and on April. 2, ordered the occupation of the Falklands. The British government under then-Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher responded by ordering a task force to retake the islands, triggering a 72-day war that led to the deaths of 907 people — 649 Argentine military personnel, 255 British military personnel, and 3 Falkland Islanders.

The loss of the war also accelerated the end of Argentina’s last military dictatorship — which came to power through a coup in 1976 — the following year. The reintroduction of democracy led to large-scale trials and sentencings of the members of the military, many of whom were convicted of crimes against humanity and received life sentences.

April 2 is a national holiday in Argentina, officially called the Day of the Veterans and Fallen of the Malvinas War, which pays tribute to the country’s soldiers that were killed, many of whom were conscripts. At that time, young men who turned 19 had to do a 12-month period of military service and were subject to later recall. Just under half of Argentines killed in the war were conscripts, who were not properly supplied with food, clothing and shelter.

For those that survived the bitter cold of the battlefields, their reintroduction back into society was painful. “Particularly in the early years, it was a complex and traumatic issue,” said María Inés Tato, director of history and war at the University of National Defense and coordinator of the Group for Historical Studies on War.

Tato said the defeat led to blame by Argentines, from top military brass down to the young conscripts.

“Upon their return from the front, veterans encountered the indifference of a society that didn’t recognize their individual sacrifice or the raw experience that marked them for life,” said Tato. “They had to face a double stigmatization. In addition to being associated with the defeat of a war that had become unpopular overnight, they were grouped into the same fate as other uniformed personnel — they were linked to illegal repression as a result of the antimilitarism of society, whose intensity has experienced ups and downs throughout the four decades since the war.”

Domestic support for the war was almost unanimous and remained so right up until defeat. Sovereignty over the Falkland Islands is a common cause in Argentina, which it has maintained since its independence from the Spanish Empire. Spain claimed possession of the islands at the time.

The first known settlements on the islands were French and date back to 1764, before the British and Spanish began to build settlements, generating tension over control of the Falklands. The British were expelled while the French agreed to leave, leading to Spanish control from the 1770s up until the end of its empire in Latin America in the 1830s.

in 1833, Britain reasserted control over the Falklands after sending two navy ships to the islands after Argentina (at that time called the United Provinces of the River Plate) refused to acknowledge Britain’s sovereignty claims and appointed a governor to the islands. Britain has maintained control over the islands ever since.

“Argentine society gave almost unanimous support to the Malvinas war,” said Tato. “The recovery of the islands garnered huge support by leaders across the entire political spectrum, trade unions, business leaders, rural producers, intellectuals and artists.”

Musicians and artists were blacklisted by the dictatorship, particularly those who played rock music. Icons such as Charly García and León Gieco were heavily censored for their lyrics while other artists went into exile. However, with the outbreak of war, the government banned English music and hoped to release a cultural value of patriotism by relaxing the censors on domestic rock.

Argentines psychologically reconciled their broad support of the war with their horror at the domestic Dirty War that the junta inflicted on its own people who were suspected of being left-wing activists or sympathizers.

“If during the war it was possible to reconcile the social rejection of the dictatorship and support for the conflict,” Tato said, “this was soon broken as opinions of the war moved from heroic deed to absolute condemnation, after which the war entered the shadows from which it has not been able to emerge.”

For countries that have recently passed through dark periods, many decide to keep the events obscured and forgotten either at the hands of the state or collectively by society.

Argentina has gone through a process of coming to terms with its recent history and keeping alive the memories of state terror. Organizations set up during the dictatorship, like the Mothers of the Plaza de Mayo, initially formed to find the forced disappearance of children, gave evidence of human rights violations that helped to convict military members.

Museums and historical sites opened up to keep the light directed on the memories of past state terror, including the Navy Mechanics School, an old military education facility known by its Spanish acronym, ESMA. Squeezed between premium real estate, the interior of the Greek-style architecture of the building housed some of the darkest memories of modern Argentina.

ESMA was one of the most notorious detention centers that was used for the torture, murder and disappearance of 5,000 people that the military dictatorship decided were a threat.

These sites of memory have helped the past to remain in the present. “The 1976-1983 period is still very much present today, with the exception of the Malvinas experience,” said Tato, “which operates as an uncomfortable reminder of a past commitment that wants to be forgotten and that needs to be critically debated and fully integrated into recent Argentine history.”

Since the war, Argentina has continued to claim sovereignty over the islands. At the international level, the United Nations annually reiterates the need for both countries to resume dialogue on the question of sovereignty, a resolution that was first adopted in 1965.

Consecutive British governments have rejected appeals to resolve the question of sovereignty of the Falklands, stating that negotiations would only take place if the islanders themselves agreed to them. The Falklands carried out a referendum in 2013, in which 99.8% of the islanders voted to remain a British territory with a turnout of 92%. Only three people voted no. Argentina’s president at the time, Cristina Fernández de Kirchner, rejected the vote, saying: “It is as if a group of squatters had voted on whether to continue illegally occupying a building.”

Subscribe to Closing Arguments

Sign up for new weekly newsletter Closing Arguments to get the latest about ongoing trials, major litigation and hot cases and rulings in courthouses around the U.S. and the world.