HOUSTON (CN) — Kenneth Hoyt didn’t disclose his occupation even as he silently considered the constitutionality of the stop: A policeman had pulled him over in a Texas shopping center and questioned him for an hour while running his name for warrants. “As a federal judge, I had no right to be treated better or worse than any other citizen. Revealing my status could have resulted in one or two extremes — better or worse,” Hoyt said.

That was in 1990. Though Hoyt had been a federal judge in Houston since 1988 when the Senate confirmed his nomination by President Ronald Reagan, he knew his and his wife’s skin color made them targets in the shopping plaza, 35 miles southwest of Austin.

There are 1,238 sitting federal judges of which 138, 11 percent, are African-American, according to the Federal Judicial Center.

Here are the stories of three black men who preside in the Southern District of Texas.

The Groundbreaker

Growing up in East Texas where he attended segregated schools, Hoyt learned that speaking out against racism could provoke a vicious backlash. He had other, more pressing concerns.

His father, a tailor and barber, could not work due to a head injury he suffered in World War II. His mother, a beautician, had to provide round-the-clock care for his father, so she could not work full time outside the home.

“As a result, at age 12, I went to work in various odd jobs to help put bread on the family table,” said Hoyt, who was born in 1948, and grew up in a home with no plumbing.

He picked cotton, harvested resin from trees, cut lawns, sold newspapers, cleaned bathrooms at his school and worked at the local country club.

With his body occupied, his mind smoldered, fixating on Uncle Sam’s indifference toward his father: Why was the government denying him a full disabled veteran’s pension?

He vowed to seek justice in court.

“At a young age, I decided I wanted to become a lawyer, to correct my dad’s injustice. I wanted the Veteran’s Administration to recognize my father’s disability and pay him the compensation he was due,” Hoyt said.

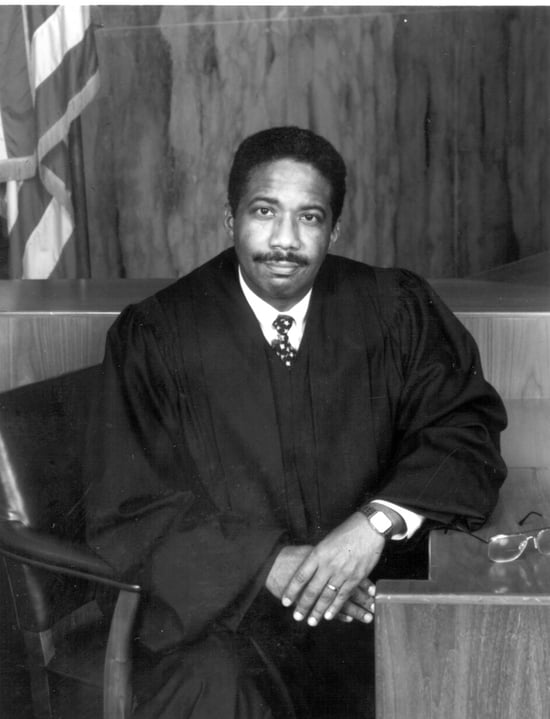

Hoyt, 70, was the first black man appointed to federal judge in the Southern District of Texas.

He is now semiretired in name only. He took senior status on his 65th birthday in March 2013, which gave him the option to reduce his caseload while still receiving his full salary.

But U.S. District Judge Lee Rosenthal, chief judge of the Southern District of Texas, said Hoyt still takes on a large caseload at Houston’s federal courthouse.

He’s also handling all the civil cases in the district’s Victoria division, where there is no resident judge in the courthouse 125 miles southwest of Houston.

“He’s a stalwart,” Rosenthal said.

The Mentor

Hoyt’s successor, Alfred Bennett, grew up as the youngest of four children of a teacher’s aide and truck driver in Ennis, 30 miles south of Dallas.

Despite the 1954 Supreme Court ruling in Brown v. Board of Education, declaring segregated schools unconstitutional, Texas took its time to comply with the law.

Bennett’s siblings attended all-black schools until 1968 or 1969, he said in an interview in his chambers at the Houston federal courthouse.

“In our family albums you’ll see second-grade pictures segregated, third-grade pictures segregated. And then all of a sudden it’s an integrated picture. So they attended the segregated schools, but by the time I was of age to come to school, the schools had already been integrated,” he said.

Bennett found his calling in high school reading about a white lawyer who agreed to represent a black man accused of raping a white woman in Alabama in the 1930s, despite the risk from the Klan, which attacked white people who helped or socialized with black people.