MEXICO CITY (CN) — Those en route north had bags, blankets and other personal belongings with them. Those who had been deported from the United States had only the clothes on their backs: the T-shirts, sweatpants and black laceless slippers that Customs and Border Protection agents gave them after confiscating all of their possessions, garments included.

But no matter how they ended up splayed out on the floor of Mexico City’s northern bus terminal Monday afternoon, these Venezuelan migrants had one thing in common: they had no idea what they were going to do next.

The news of the change in U.S. border policy to offer humanitarian parole to 24,000 Venezuelans and return the rest to Mexico had hit them all like a ton of bricks. They had spent a month or more braving jungles and other dangers to get here under the notion that they would be able to wait out asylum hearings north of the U.S.-Mexico border.

Now, with that avenue blocked thanks to the Trump-era public health policy known as Title 42, and little assistance provided by Mexican authorities, these migrants are scared to even leave the bus terminal. Many have no resources to go anywhere even if they wanted to.

“We don’t know ... We don’t know what…,” said Joiner Acosta, exasperated. “And how does one even return home without any money?”

Acosta, 36, recalled harrowing images from his time crossing the thick, dangerous jungle between Columbia and Panama known as the Darién Gap.

“It was horrible, many deaths, people falling, having heart attacks, being taken by the river, you have to cross the river like a hundred times,” said Acosta. “It’s terrible, terrible.”

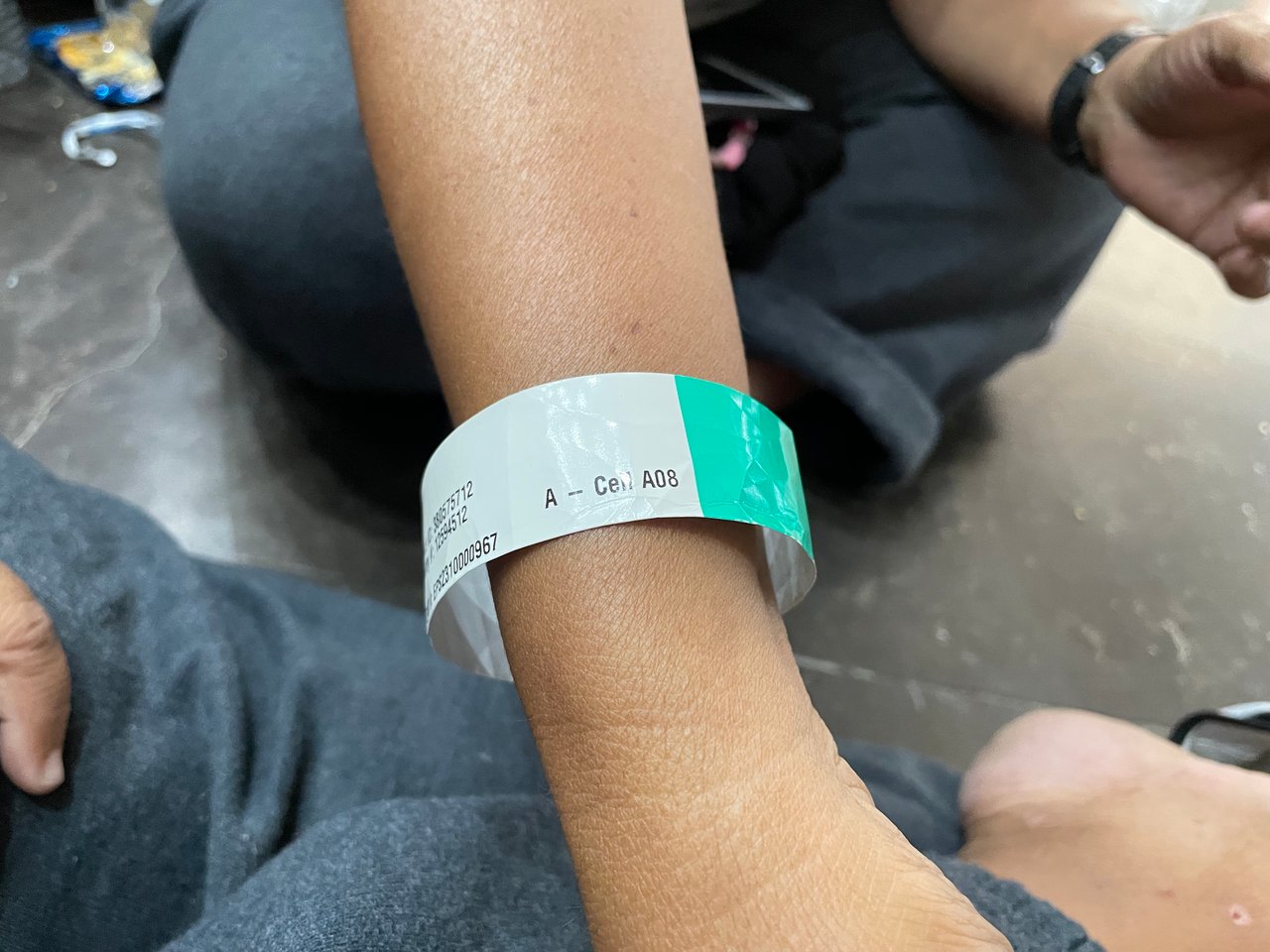

A few feet away sat 46-year-old Marbi, who preferred to not give her last name after her deportation, and two friends who had also been detained and deported to Mexico City.

“They had us in there like prisoners, our hands in handcuffs chained to others on our feet,” she said, showing where the metal had eaten into the skin of her ankles.

Although she and her friends entered the U.S. on Oct. 10, two days before the announcement of the policy change, they spent seven days in detention before being sent to Mexico.

“They didn’t let us shower for six days,” she said.

“They kicked us out of the country without any of our things,” said a friend of Marbi’s who preferred not to give any name at all. “Some of us sold our homes and other belongings to come up here — and we entered before the 12th — just for them to toss us out.”

The policy change has left Venezuelan migrants with very few options, one of which is applying for refugee status in Mexico.

“As the bilateral agreement dictates, we are going to attend in a humanitarian way to those who are turned away from the United States under Title 42,” said Andrés Ramírez Silva, director of Mexico’s refugee commission Comar.

But migrants must be aware of their eligibility for seeking asylum in Mexico and actively seek it out. Last year, an unprecedented influx of migrants from Haiti put the agency’s dire lack of funding and resources in desperate relief and nearly collapsed it entirely.

However, while Ramírez foresees potential difficulties dealing with another influx of asylum seekers thanks to the agreement between the U.S. and Mexico, he does not expect the situation to get so serious this time around.

“It won’t turn into a crisis like we saw with the Haitian migrants,” he told Courthouse News.

Comar has changed its policy in order to make the process easier for those applying for refugee status now. Whereas in the past, an asylum seeker had to remain in the state in which their application was submitted, the commission will now allow them to continue their applications even if they move to other parts of Mexico in the process.

The humanitarian parole program could eventually act as a deterrent to those thinking of leaving Venezuela in the future, Ramírez said, but added that it is still too early to know the full effects of the policy.

“It’s not necessarily a problem, we’ll see how things go,” he said.

While deterrence is one eventuality, another very possible outcome of the policy change is that more Venezuelan migrants will resort to organized crime to attempt to enter the U.S., according to Aaron Reichlin-Melnick, policy counsel and border issues specialist at the American Immigration Council.

“A lot of Venezuelans are going to have to be making a lot of difficult decisions in the coming weeks, especially those who have already left,” he said.

As with previous immigration policy changes, like former President Donald Trump’s Remain in Mexico initiative and its relaunch under the Biden administration, the current reality on the ground is one of great uncertainty for migrants.

Title 42 has been used over 2.3 million times to turn asylum seekers away from the southern border, according to the latest CBP data. In March, Human Rights First had linked nearly 10,000 reports of violent crimes like rape, kidnapping and torture on people expelled to Mexico under the policy.

Bad relations between Washington and Caracas limited its use on Venezuelan asylum seekers, but last week’s agreement with Mexico allows the Biden administration to use what was once a largely unknown health code to expel more migrants from the country. The change came just weeks after the president told 60 Minutes that the pandemic was over in September.

“At this point, the charade that it is anything other than a migration tool has basically been dropped,” said Reichlin-Melnick. “The Biden administration is not even attempting to justify their use of Title 42 in this way, they are simply and very openly declaring that the expulsions are being carried out for immigration deterrence purposes.”

Subscribe to Closing Arguments

Sign up for new weekly newsletter Closing Arguments to get the latest about ongoing trials, major litigation and hot cases and rulings in courthouses around the U.S. and the world.