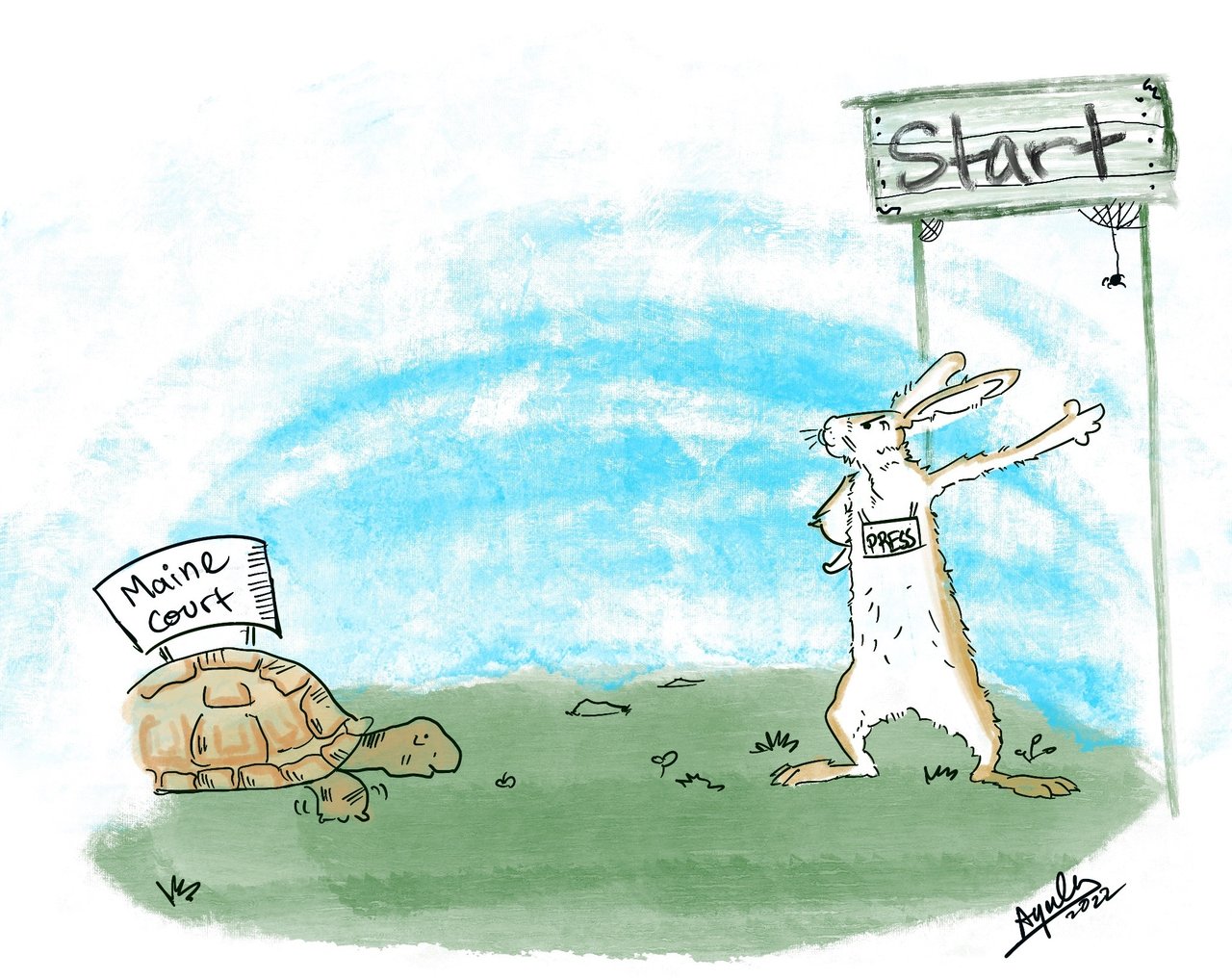

A First Circuit panel last week heard our appeal of a Maine federal judge’s decision to dismiss our First Amendment case on the pleadings.

Even though the nation has emerged into the light after a two-year hibernation, the First Circuit courtroom where the judges heard the arguments was dark to press and public.

With a great interest in the questions and answers of oral argument, I wanted to see the judges. But I could not. I was pretty sure which judges were asking questions but could not be certain. The same policy was followed in the Eighth Circuit recently.

Normally I order a transcript of all substantive hearings in our cases. In the trial court, that is a very straight-forward process where you simply ask the court reporter to prepare a transcript and pay for it.

I was surprised to find out that there is no such mechanism at the appellate level. A recording is put online but not the transcript. One might think that the hearing is small potatoes compared to the opinion. But the questions and answers that precede the opinion are highly instructive.

In the clearest, cleanest, most incisive opinion so far on the issue of state court clerks withholding access to new filings in defiance of First Amendment rulings, Judge Christina Reiss in Vermont quoted one of her own points made in the furnace of oral argument. Held a full six months ago, that hearing was open.

The issue in the case over access in Bangor is the clerk’s practice of blocking access to new filings while they are docketed, contrary to tradition, a practice that makes the news stale, much like bread a day or two after it’s baked. Using the tape record, I reconstructed key parts of the argument.

The First Circuit panel spent much of an hour-long argument suggesting that the clerk needs to give an imprimatur of some kind for a complaint to be considered a complaint.

Chief Judge David Barron: For First Amendment purposes, I need some way of defining what is a civil complaint.

Barbara Smith with Bryan Cave for Courthouse News: When you log onto the e-filing system and one of the dropdown menus says, ‘What type of document this is,’ and you click ‘civil complaint’ and submit it, we are asking for access to those documents.

Barron: Are there complaints that are filed that, prior to the processing that Maine wants to subject every complaint to, count for purposes of stopping the statute of limitation.

Smith: When the complaint is filed, that is when the statute of limitations clock stops.

Barron: What does that mean.

Smith: At the point it is submitted by the attorney, that is the point at which it is filed.

At the end of Smith’s opening argument, Judge O. Rogeriee Thompson, in a gravelly voice full of character, asked a set of direct questions that were pivotal in establishing when the right of access attaches.

Thompson: Is there anything such as the filing of a nonconforming complaint that gets returned.

Smith: There are complaints that are filed and rejected because the attorney fails to include their Maine bar number or maybe they have failed to sign the complaint. The processing that the clerk does looks for those things and can reject those complaints.

Thompson: is that considered a complaint.

Smith: It is considered a filed complaint that the clerk then sends back to be corrected by the filer. For the purpose of the statute of limitations and the beginning of the case, however, it’s the filing of that initial complaint, even if it is later rejected and refiled, that counts. That’s why access to that initially filed complaint, even if there is some sort of ministerial problem with it, is the point at which the First Amendment right of access attaches.

Chief Judge Barron then presses Maine’s lawyer as to when the right of access attaches. This is a key issue in the battles over First Amendment access, because once the right attaches, the government must then overcome a presumption in favor of access by showing an overriding interest and a narrowly tailored restriction.

Barron: Are you saying there is no First Amendment scrutiny until you designate it as a complaint.

Assistant Attorney General Thomas Knowlton: What we’re saying is that the time for providing access that would be operative under the First Amendment would be the time from when it is first submitted to the court to when it’s provided to the public.

Barron: You’re conceding it’s a judicial record on submission.

The argument returned to Smith on rebuttal. The chief judge continues to push the notion that a complaint is not really a complaint until a clerk gives it the official imprimatur. And even though Maine’s lawyer is not making this argument, Judge Sandra Lynch presses the same idea, that the clerk, not the lawyer. makes a complaint a complaint. This would support the notion that the clerk must docket, or process, the complaint before it can be seen by the press.

Smith: Chief Judge Barron, to respond to your question about when the statute of limitations and filing deadlines attach, that’s at the record appendix 294 to 295, it’s RX 35b that says that for an electronically submitted document any filing deadline or statute of limitations is the initial filing even if the document is later rejected and refiled.

Lynch: And refiled, meaning that it’s later accepted for filing, right.

Smith: That’s right, it’s filed, it goes through the processing, it’s rejected and refiled, and none the less, for the purposes of the statute of limitations —

Lynch: And accepted for refiling.

Smith: Correct, so in this circumstance —

Barron: The difficulty is that essentially, these nonconforming complaints are contingently complaints at the moment of their nonconforming filing. Because we just don’t know whether there will be a complaint at all until we see whether they conform. It is also the case that unlike some documents, they have the chance of being a complaint upon filing.

Smith: I don’t think that’s the right way to look at it, Judge Barron. I think the right way to look at it is that when the attorney walks into the courthouse or submits the e-filing button that says ‘I’m a filing a complaint’ — that’s a complaint. If it’s rejected for ministerial reasons and later refiled, I think we are still entitled to access to that nonconforming complaint.

Good stuff. We could sure use a court reporter’s transcript.

Subscribe to our columns

Want new op-eds sent directly to your inbox? Subscribe below!