(CN) — Already named the toughest bacteria on Earth by the Guinness Book of World Records, Deinoccal radiodurans has shattered a new galactic record: longest known survival in open space.

A team of Japanese researchers interested in panspermia — the theory that life can transfer or has transferred from one planet to another — found the UV-resistant bacteria survived at three years on the side of the International Space Station, and could possibly live long enough in space to make the trip to Mars.

"The results suggest that radioresistant Deinococcus could survive during the travel from Earth to Mars and vice versa, which is several months or years in the shortest orbit," said Dr. Akihiko Yamagishi, a professor at Tokyo University of Pharmacy and Life Sciences and principal investigator of the space mission Tanpopo.

Rocky panspermia, or lithopanspermia, describes the organisms that might survive inside a protective barrier like in an asteroid. Research published in the journal Frontiers on Wednesday, however, is the first to investigate the viability of microbes in open space, without any protective shell.

"The origin of life on Earth is the biggest mystery of human beings,” Yamagishi said in a statement. “Scientists can have totally different points of view on the matter. Some think that life is very rare and happened only once in the universe, while others think that life can happen on every suitable planet. If panspermia is possible, life must exist much more often than we previously thought."

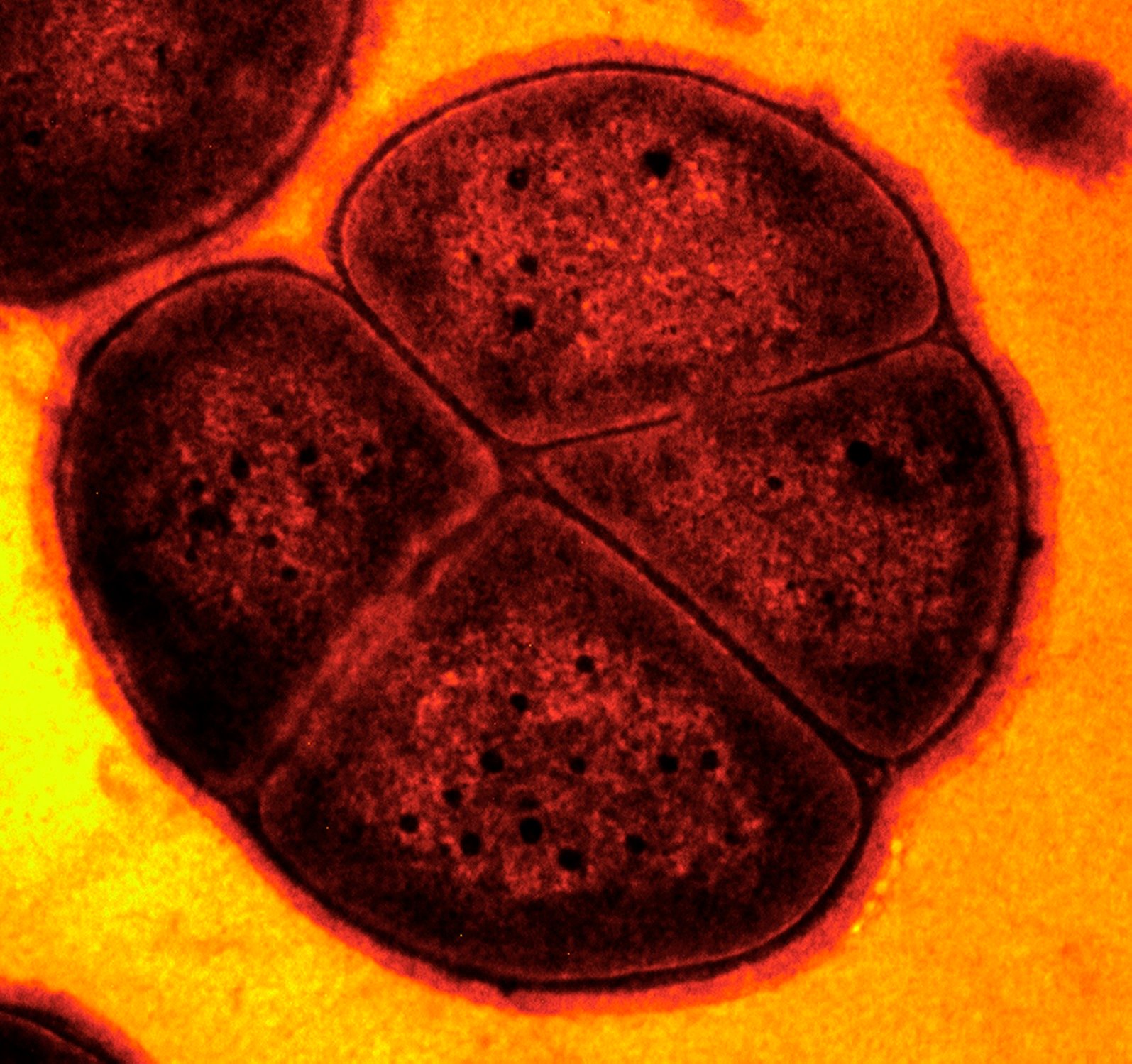

With a Latin name roughly translating to “radioactive resistant berry,” Deinoccal radiodurans was discovered in 1956 in a can of meat exposed to radiation levels thought capable of destroying any and all life forms. But D. radiodurans is not only able to repair radiation-damaged DNA, it also forms red or pink berry-like colonies; as the outer layers of the colony die, the dead become a protective covering for survivors at the core.

To test whether this barrier was strong enough to protect D. radiodurans cells from the intense ultraviolet light radiation of open space, researchers attached aluminum plates with dried out cell pellets to the International Space Station. Colony thickness ranged from 100 microns to 1,000 microns and space exposure spanned three years.

Alongside D. radiodurans, the experiment included the two other species of Deinococcal bacteria, D. aerius and D. aetherius.

In 2016, the space-faring spores launched on the Japanese Tanpopo space mission nearly 250 miles above Earth.

The first set of samples returned to Earth on SpaceX9 in August 2016. SpaceX12 delivered the second set in September 2017 and SpaceX15 brought the final samples in August 2018.

While single layers of the bacteria died, dehydrated colonies just 1 millimeter in diameter survived 1,126 days in space. Researchers estimate D. radiodurans shielded just by 0.5 millimeter of their own cells can survive 15 to 45 years in space, or 48 years if left in the dark.

While this research suggests the microbes could survive the trip from Mars to Earth in open space, Yamagishi cautioned that any organism would still need to survive ejection from one planet and landing on another, not to mention how infrequently the planets’ orbits a line near each other.

Whether this little microbe could survive the trip to another Earth-like planet, Yamagishi said via email, “No, I don’t think so. The nearest planet was found at about 4 light-years distance. It takes tens of thousands of years [to make that trip] using current manmade rockets. Deinococcus can survive tens of years shielded from UV, which is far shorter than the time needed to travel to next exoplanet.”

Nevertheless, he said he hopes to discover microbes in outer space.

"If we can search and catch microbes traveling between planets, it would be great,” Yamagishi wrote. “The search for life from Earth on the surface of the moon may be easier. The search for life on the surface of Mars is far more important. If we were to find life forms on Mars, we will be able to test the similarity between Mars and Earth life forms."

The Japan Society for the Promotion of Science funded this research.

Subscribe to Closing Arguments

Sign up for new weekly newsletter Closing Arguments to get the latest about ongoing trials, major litigation and hot cases and rulings in courthouses around the U.S. and the world.