(CN) — According to findings from a study released this week, scientists have confirmed that mysterious stone forests are formed by flowing water eroding the landscape, creating a unique rocky terrain with needle-sharp points.

The study was conducted by scientists from New York University, including Leif Ristroph, an associate professor at NYU’s Courant Institute of Mathematical Sciences, Michael Shelley, also a professor at the Courant Institute, Jinzi Mac Huang, an NYU doctoral student, and Joshua Tong, an NYU undergraduate.

Details are published in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, where the researchers describe how they performed simulations to demonstrate how these fantasy-like structures may have been created.

Stone forests are vast landscapes of massive limestone rocks that almost look like giant petrified trees, giving the illusion of a forest of stone. They are incredibly striking in appearance and attract a steady flow of tourism, but their origins have long been a mystery to science.

The most famous stone forests can be found in China and Madagascar, but are seen dispersed all over the world, and each have rich cultural significance.

The Yunnan province in southwestern China is home to the Stone Forest of Shilin, approximately 270 million years old and over 180 miles large. It is generally believed that over the years, the forest got its shape from seismic activity and erosion from wind and water.

The landscape is so large and labyrinth-like, it is split into many smaller parks, each with distinct landmarks including caves, waterfalls, and even an underground river. One landmark is known as the Ashima stone, which holds a story of a girl who turned to stone and attracts an annual festival for the locals.

Across the globe in the Melaky region of northwest Madagascar is the Tsingy De Bemaraha National Park. It sits atop two formations called the Great Tsingy and the Little Tsingy.

The Tsingys are plateaus where groundwater has formed complex caverns with horizontal and vertical erosion patterns. The word Tsingy translates from Malagasy to English as “where one cannot walk barefoot” referring to the badlands of this region.

In order to figure out how the pointed pinnacles in the stone forests are formed, the team looked at karst topography, which is the result of the erosion of soluble rocks like limestone.

Limestone covers approximately 10% of Earth and is incredibly porous. It easily decays when exposed to acidity, and rainwater is a big culprit in this phenomenon.

Rain is naturally acidic due to carbon dioxide in the atmosphere, and although it is a very weak acid, once it comes into contact with the calcite in the stone it begins to dissolve the mineral.

This process is responsible for the famous underground limestone caves — as the rainwater percolates through the soil, it begins to break up the limestone enough to form large openings. These limestone caves can function as carbonate aquifers, producing and containing freshwater for hundreds of millions of people.

First, the team used a combination of computer simulations and a mathematical model of their design, which replicated what happens when rocks such as these begin to dissolve. Secondly, they performed experiments in the Applied Mathematics Lab at NYU to further test their simulations.

In these experiments, they used a block of candy that contained internal pores and was similar in solubility to limestone to try to create their own karst topography. They found that their results were virtually identical to those from the simulation.

After placing the sugar-block in an underwater tank, it instantly started to dissolve naturally into a spiked “sugar forest” with the same pinnacle shapes seen in the stone forests, confirming their suspicions.

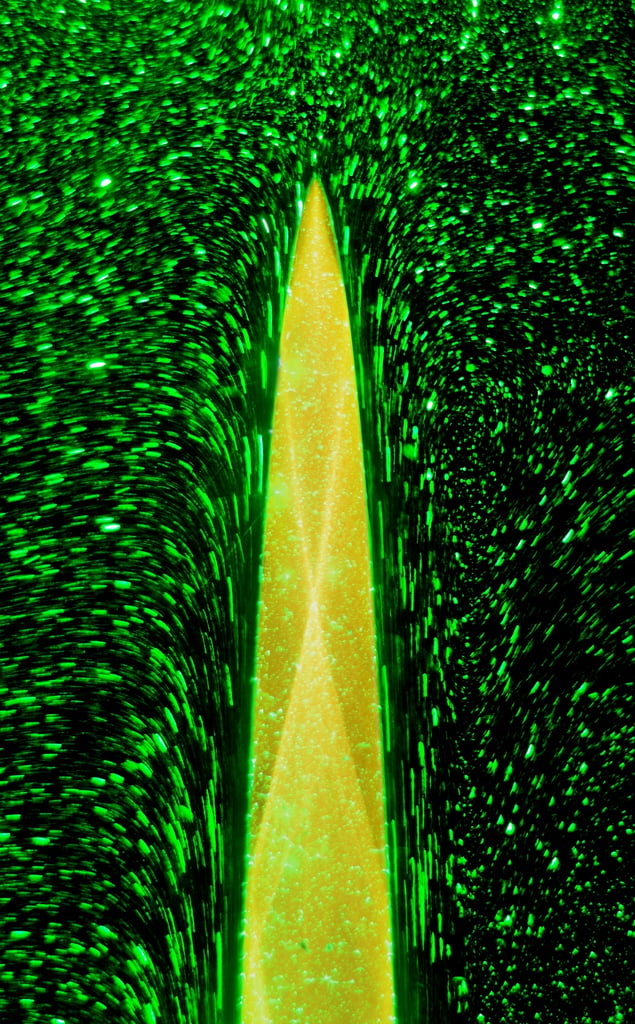

Furthermore, they were able to see the flows of sugar coming off of the pinnacles by shining green lasers down from above and adding microparticles to the water. They could see how the flows sunk to the bottom of the tank due to gravity as they dissolved into water.

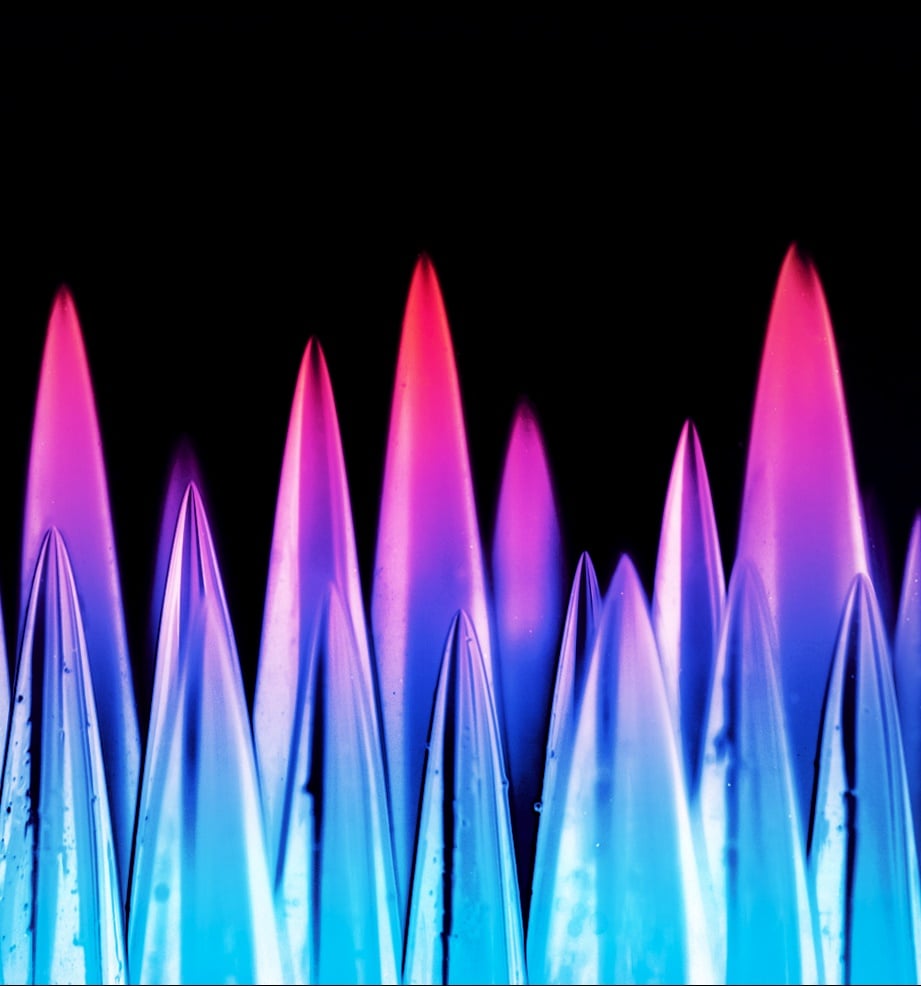

"This work reveals a mechanism that explains how these sharply pointed rock spires, a source of wonder for centuries, come to be," Ristroph said. "Through a series of simulations and experiments, we show how flowing water carves ultra-sharp spikes in landforms.”

The findings suggest that these structures are formed underwater and emerge over long periods of time when the crust beneath it lifts above sea level. The authors note that the results of their work hold great potential to assist in the manufacturing of other important, sharp-pointed objects, such as micro-needles and probes necessary for some medical procedures.

-

(Ristroph et al. / PNAS) -

(Ristroph et al. / PNAS)

Subscribe to Closing Arguments

Sign up for new weekly newsletter Closing Arguments to get the latest about ongoing trials, major litigation and hot cases and rulings in courthouses around the U.S. and the world.