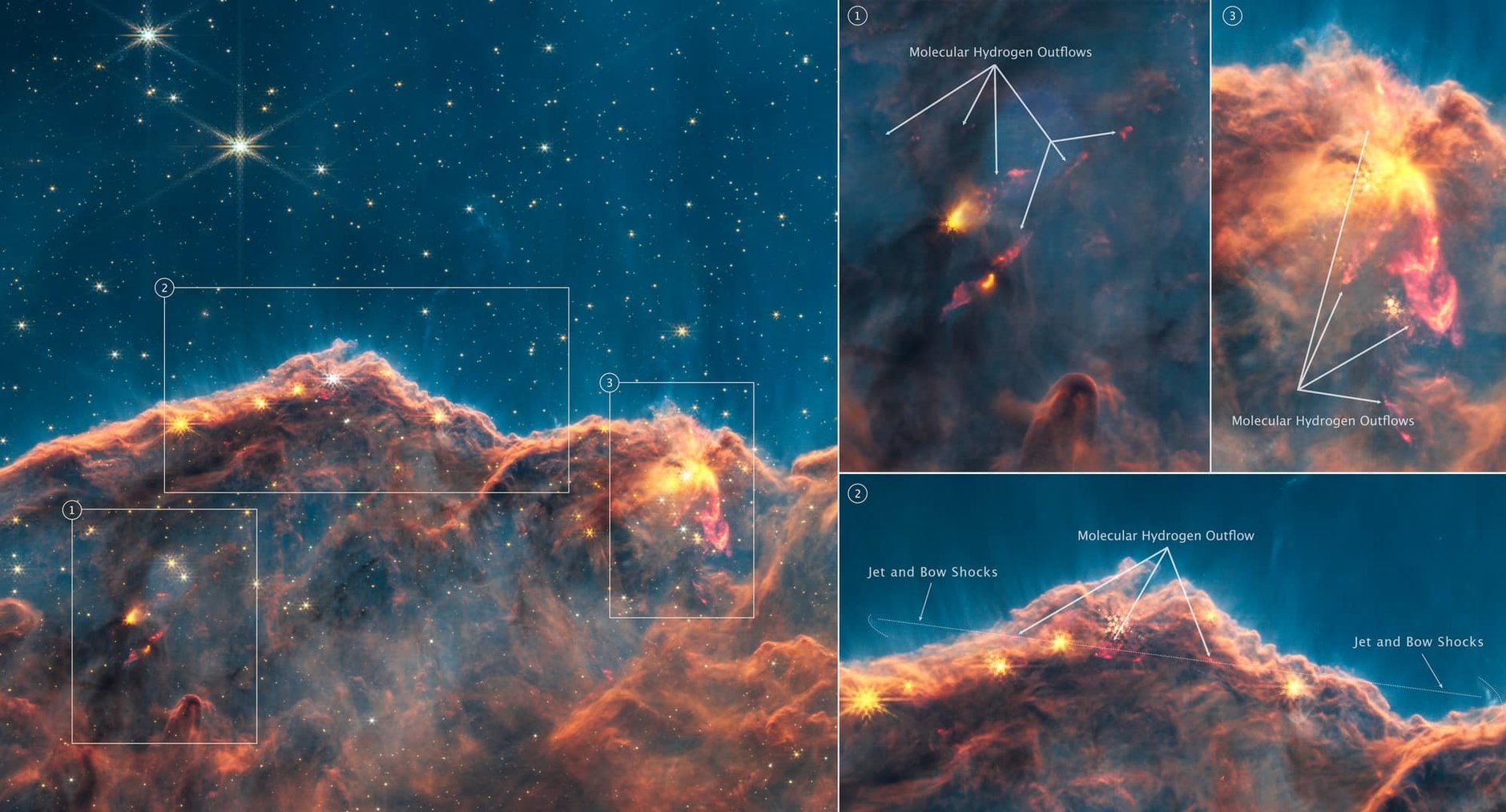

(CN) — NASA scientists announced Thursday that they had discovered evidence of two dozen previously unknown protostars wrapped within the gasses of a distant nebula. The starlets had long hidden in plain sight, only recently identified via close examination of one of the first images taken by the James Webb Space Telescope.

Dubbed "Cosmic Cliffs" and released publicly this past July, the image shows an active star-forming region known as NGC 3324 in the Carina Nebula, itself a massive cloud of gas and dust in the Carina-Sagittarius Arm of the Milky Way Galaxy. The nebula is close enough to Earth - some 8,500 light years away - to be seen with the naked eye, but is only visible in the southern hemisphere.

Ironically, the same colorful gas and dust that makes the nebula an attractive target for amateur southern skywatchers also impedes astronomers trying to detect stars and other celestial bodies hidden within the stellar fog. Even the Hubble Space Telescope, which has studied Carina for years, has difficulty peering through the thick clouds.

The Webb telescope, which captures images in infrared light, has a much easier time of things. The long wavelengths of infrared light penetrate gas clouds more easily than light in the visible spectrum, revealing outflows of molecular hydrogen - a tell-tale sign of new star formation.

"We're looking for red and orange streaks... we sometimes see clumps that let us know there's more than one star forming," said Rice University astronomer Megan Reiter in an interview.

Reiter is one of the scientists who led the Cosmic Cliffs analysis. Her and other astronomers' findings on NGC 3324 were published earlier this month in the British science journal Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society.

She went on to explain that the mechanism which produces the outflow jets is still poorly understood. As her colleague and study co-author Nathan Smith pointed out, they only occur during a very short-lived phase of star formation, a process that can take millions, even hundreds of millions of years.

“Jets like these are signposts for the most exciting part of the star formation process," Smith, an astronomer for the University of Arizona in Tucson, said in prepared remarks to NASA. "We only see them during a brief window of time when the protostar is actively accreting,”

"Actively accreting" refers to when clouds of dust and hydrogen gas first begin to accumulate under their own gravity. As the gaseous clumps grow, they attract even more material, becoming progressively hotter, denser and more spherical. Eventually, a fusion reaction sparks in the core of the accumulated material, signaling the birth of a new main-sequence star.

But even before hydrogen-helium fusion sparks, the stars-to-be will have developed their own electromagnetic fields and spheres of gravitational influence. The material drawn in by a protostar's gravity forms what's known as an accretion disk, a flat plane of material which can eventually coalesce into planets and asteroids. Simultaneously, the protostar's magnetic field ionizes the inflowing gas, giving it an electric charge.

Reiter said the interaction of these complex forces may be what forms the outflow jets she and her team observed

"We think the jets are leeching energy from the accretion disk, but in order for the material to be shot out, it needs to lose angular momentum," Reiter said, referring to the inertia of material revolving around the protostar.

The forming star's electromagnetic field may then provide an extra push for the outflow of material, repelling the ionized gas in great streams at its magnetic poles.

"As young stars gather material from the gas and dust that surround them, most also eject a fraction of that material back out again from their polar regions in jets and outflows," NASA said in a press release accompanying Thursday's announcement. "These jets then act like a snowplow, bulldozing into the surrounding environment. Visible in Webb’s observations is the molecular hydrogen getting swept up and excited by these jets."

The entire period during which the jets are visible may last only a few thousand years. This makes their discovery all the more precious, especially since many of the protostars seen in the Cosmic Cliffs are likely to develop into low-mass stars like our own sun.

“It opens the door for what’s going to be possible in terms of looking at these populations of newborn stars in fairly typical environments of the universe that have been invisible up until the James Webb Space Telescope,” Reiter told NASA. “Now we know where to look next to explore what variables are important for the formation of Sun-like stars.”

In comments to Courthouse News, Reiter added that finding the protostars in NGC 3324 was like stumbling across "hidden treasure" – unexpected, but a boon to our growing understanding of star formation in the Milky Way.

"What we found really interesting in Cosmic Cliffs is... we weren't looking there for so much star formation," Reiter said. "But there they are regardless. New stars forming."

Subscribe to Closing Arguments

Sign up for new weekly newsletter Closing Arguments to get the latest about ongoing trials, major litigation and hot cases and rulings in courthouses around the U.S. and the world.