RICHMOND, Va. (CN) — Loretta Tillman, 60, remembers her first day of fifth grade in 1970, when she and about 50 other black students arrived at a previously all-white school on the Southside of Richmond, Virginia.

“Oh my goodness,” she remembered thinking, getting out of a city bus — not a school bus, because the system hadn’t procured those yet for newly established busing plans — and walking inside her new school.

“These are white people, and what are we doing in a white school?”

While Tillman’s parents worked to keep the public fight against school integration — a fight for which she was involuntarily on the front lines — out of her line of sight, she was familiar with the battle cry used by segregationists to keep white schools white: Save our neighborhood schools.

So when she found out Republican Virginia state Sen. Glen Sturtevant — who is up for reelection this fall — spent the first day of the 2019 school year distributing fliers with “Save our Neighborhood Schools” printed in big letters, she let out a heavy sigh.

“What is old is new again,” she said.

School segregation in Richmond, and more broadly across Virginia, is among the darkest points in the state’s long and tortured history with race. After the unanimous U.S. Supreme Court ruling in Brown vs. Board of Education made school segregation illegal in 1954, it did not take long for Virginia legislators to create new barriers for black children to get an education.

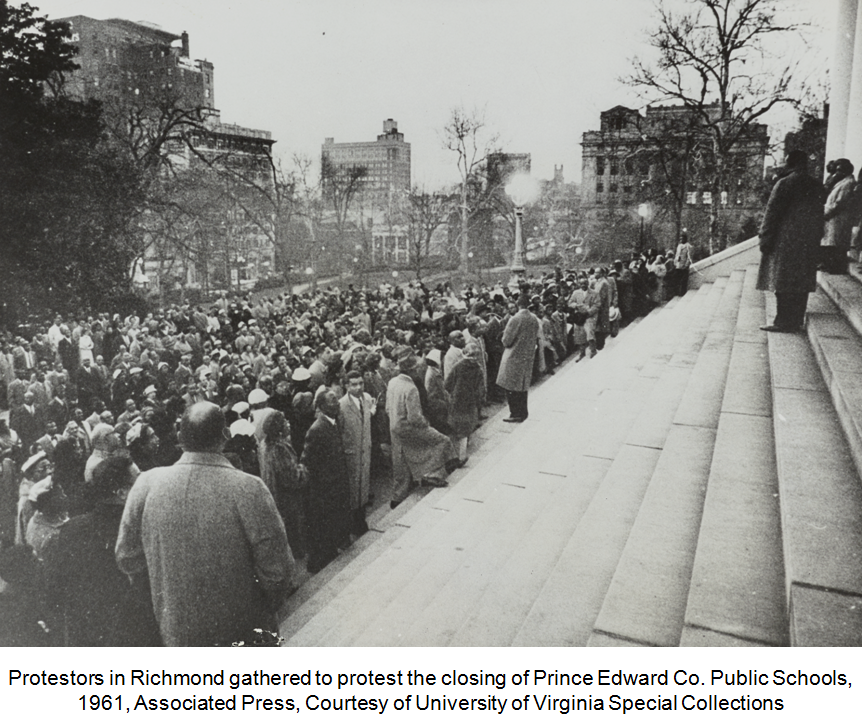

This was best manifested in what became known as “Mass Resistance,” an effort by several counties that closed their public schools entirely rather than allow black students to attend white schools. While the Virginia General Assembly ended the policy, officially in 1959, some counties continued to “resist” until 1968, when the U.S. Supreme Court stepped in again and forced the last county to reopen.

But even when school systems began to integrate, busing systems that brought black students into white schools were decried as harming white students and burdening white neighborhoods.

Woody Holton, a history professor at the University of South Carolina, also was familiar with the struggle: His father was Virginia Gov. Linwood Holton, who spearhead desegregation efforts when he took office in 1970.

To set an example, Gov. Holton sent his children to local, mostly black public schools.

Woody remembered growing up in the governor’s mansion in downtown Richmond, just a stone's throw from the General Assembly building. He recalled an incident when protesters came to the mansion in a truck with “Impeach Governor Holton” written on the side. They handed Woody, who was playing on the lawn at the time, a box of letters telling his father to abandon his desegregation efforts. A tween-aged Woody asked the protesters what “impeach” meant.

“They said it meant ‘pray for,’” he recalled, in a recent interview.

He dragged the box inside and asked his father the same question. His dad told him it meant to remove him from office. The local paper, which also pushed a desegregation agenda, used a photo of young Woody dragging the box inside on the front page the next day.

Even at such a young age, Woody said, he felt used.

And he too was shocked at Sturtevant’s use of the term “Save our Neighborhood Schools” in 2019.

“That wasn’t a slogan from 1970, that was the slogan,” he said.

“That wasn’t a slogan from 1970, that was the slogan,” he said. According to Facebook posts by parents and school board members, Sturtevant distributed the fliers the first day of school to parents as they were dropping off their kids for class. One flier says the rezoning proposal would undo parents’ efforts to have their children attend schools they explicitly moved to be close to, and would force children to take longer bus rides or burden working families who drop off their kids on the way to work.

According to Facebook posts by parents and school board members, Sturtevant distributed the fliers the first day of school to parents as they were dropping off their kids for class. One flier says the rezoning proposal would undo parents’ efforts to have their children attend schools they explicitly moved to be close to, and would force children to take longer bus rides or burden working families who drop off their kids on the way to work. Many mirrored Tillman’s story, with one subject describing a two-hour bus ride from home to an integrated school.

Many mirrored Tillman’s story, with one subject describing a two-hour bus ride from home to an integrated school.