BROOKLYN, N.Y. (CN) - In July 1846 the Brooklyn Eagle published an essay from its new editor, 27-year-old Walt Whitman, describing a blissful scene in which 30,000 men, women and children gathered on an old Continental Army fort to watch fireworks across the East River in Manhattan.

“Imagine the high summit of the old Fort, with ceaseless but mild sea breezes dallying round it; not a taint of streets or close human dwellings; but the moist fresh odor of dew-sprinkled grass, instead. Imagine a sweep of many acres, partly spread in gracefully sloping plains and partly broken into knolls and abrupt elevations, with here and there little dells—and crowning all, the great flattened apex of the hill itself. Imagine all this on the borders of a seventy-thousand-souled city—and not level to the city, but lifted out from it, as it were, and hung between heaven and earth.”

Printed more than 50 years before Brooklyn was incorporated as a borough of New York City, the essay was one of multiple calls by Whitman that argued for the space to be turned into a park. In 1849, he got his wish.

Today, over a century after Whitman’s death, passionate voices continue to advocate for Fort Greene Park as they envision it — this time in opposition to changes proposed by the New York City Department of Parks and Recreation.

Fort Greene Park was one of eight spaces selected for a facelift in 2016 as part of Mayor Bill de Blasio’s “Parks Without Borders.” The project aims to make parks more open, accessible, useful and integrated with the city.

At Fort Greene, just over a mile from the Brooklyn Waterfront, the project calls for removing several dozen mature trees and a stone wall, flattening beveled mounds added by renowned landscape architect AE Bye in the 1970s, and building a wide, flat promenade in the northwest corner to allow for an unobstructed view of the 149-foot-high Prison Ship Martyrs’ Monument.

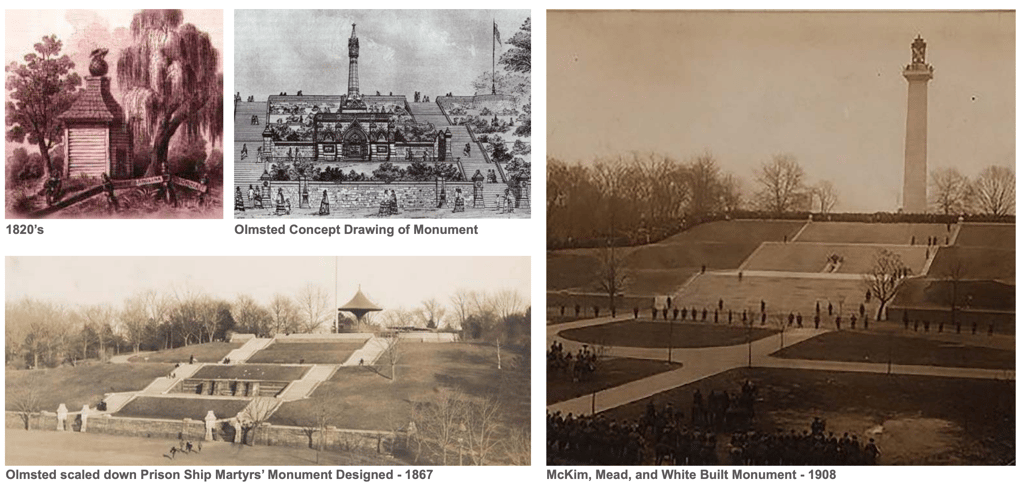

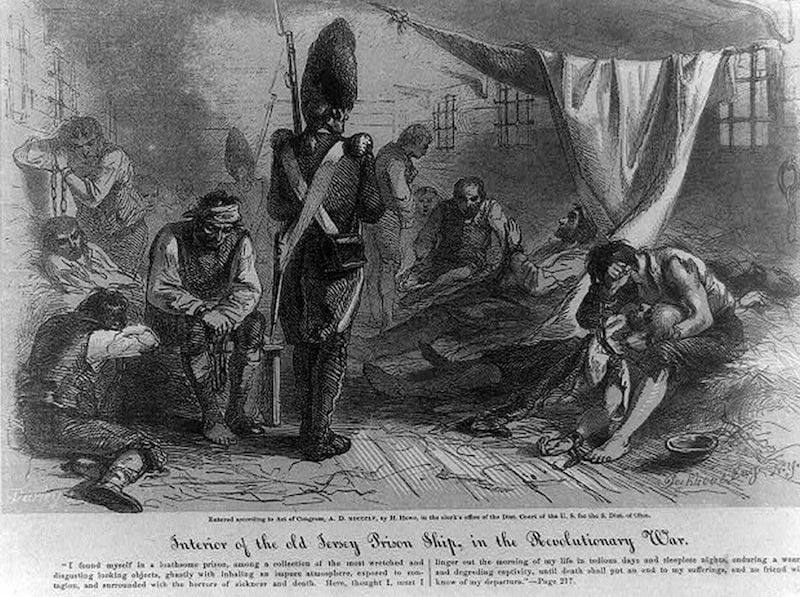

Designed in the early 1900s by the architecture firm McKim, Mead and White, the towering column honors the 11,500 people who died grisly deaths on British prison ships after the Americans’ defeat in the Battle of Long Island, also known as the Battle of Brooklyn, in the earliest days of the Revolutionary War.

The park, as Whitman explained, served as a fort during the war, and some of the prisoners’ remains were buried there in a crypt.

For community members today, the commitment to preserving this rich history has stirred fierce opposition to what is estimated to be a $10.5 million makeover.

From clockwise: "Interior of the old Jersey Prison Ship in the Revolutionary War"; a door at the base of the Prison Ship Martyrs’ Monument in Brooklyn's Fort Greene Park, a memorial to 11,500 men and women who died on British prison ships during the Revolutionary War; a beveled mound designed by landscape architect AE Bye, which would be removed as part of a renovation plan for Fort Greene Park in Brooklyn. (Photos by AMANDA OTTAWAY/Courthouse News Service)

The Sierra Club, Friends of Fort Greene Park and several individuals brought one such challenge on Feb. 15 in Manhattan Supreme Court, accusing the Parks Department of failing to publicly consider how its planned renovations will affect the environment.

“They’ve totally ignored SEQRA,” attorney Richard Lippes said in a phone interview, using an abbreviation for New York’s Environmental Quality Review Act. “They haven’t indicated that it doesn’t apply. They’ve just ignored it completely.”

Though NYC Parks spokeswoman Mae Ferguson declined to comment on pending litigation, she emphasized that the new features coming to Fort Greene were “explicitly requested and approved” by officials, the community board and the park’s neighbors.