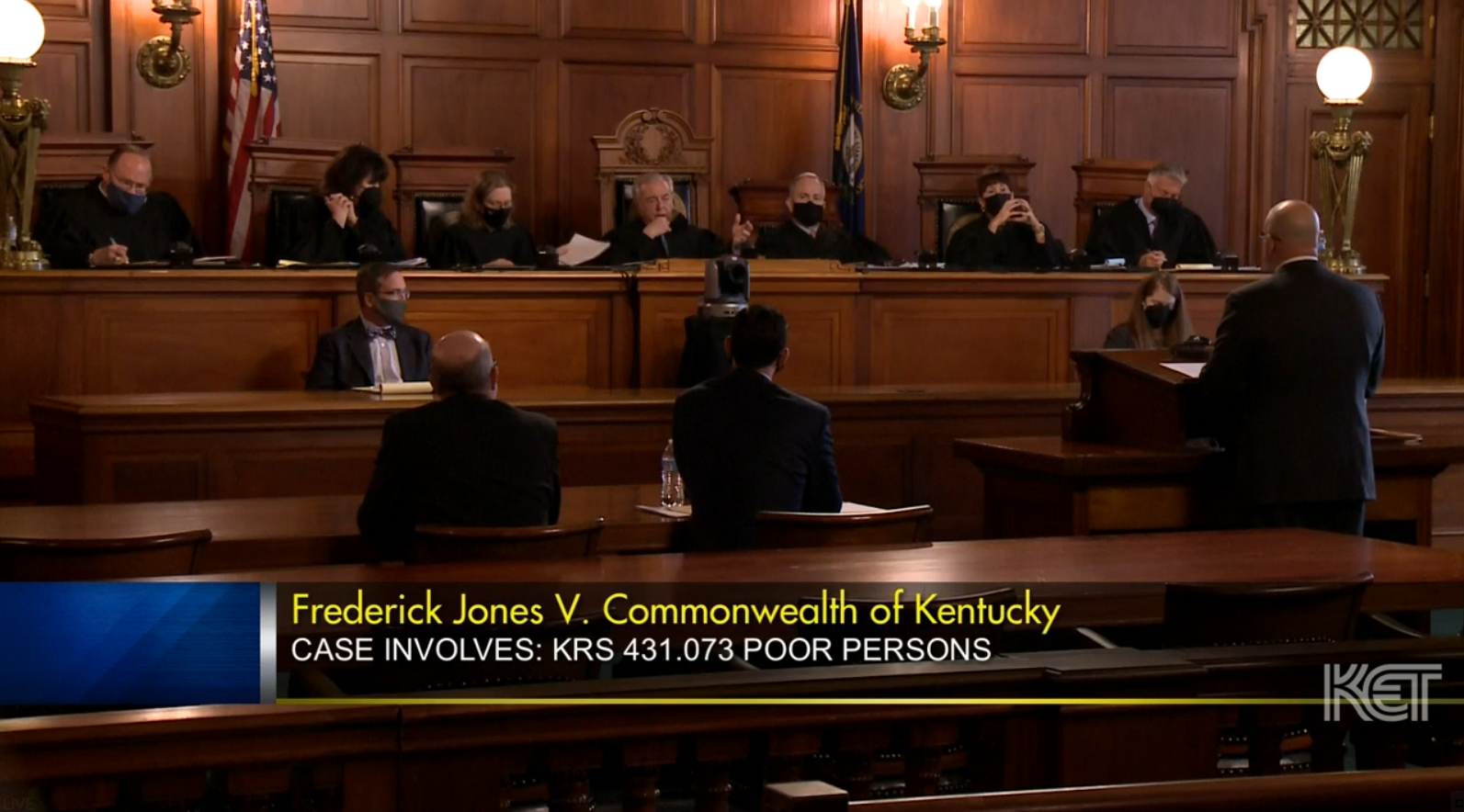

FRANKFORT, Ky. (CN) — The Kentucky Supreme Court heard oral arguments Wednesday over whether the state’s courts can waive fees for indigent people who seek to have their criminal convictions expunged.

The origins of the case date back to 1998, when Frederick Jones of Louisville pleaded guilty to a theft charge. In 2018, Jones sought to have the felony expunged from his record but did not pay the required filing fee.

Instead of paying the fee, Jones sought an order from the trial court that he would not have to pay the $500 fee due to financial hardship. The court denied the request, ruling the fee was considered an elective service that is not covered under the state’s in forma pauperis, or IFP, statute, which is used to seek fee waivers on the basis of indigency.

The Kentucky Court of Appeals upheld the ruling and found that Jones’ due process and equal protection claims also failed on the merits. Jones appealed that decision to the Kentucky Supreme Court in Frankfort.

During the roughly 40-minute hearing Wednesday, Jones' attorney Michael Abate argued before the seven-judge panel that the fee associated with expunging a criminal conviction is unique in the state’s legal framework, and is unfair to individuals who are suffering financially and seeking to have those convictions removed from their record.

“The question in this case is whether indigent litigants are denied their right to seek expungements simply because they cannot pay the fee prescribed by the General Assembly,” Abate said. “This is a question of exceptional importance to thousands of Kentuckians across the commonwealth who have completed sentences, are eligible for expungements but cannot obtain them because they cannot afford to file for one.”

While Jones was required to pay a $500 fee when he applied for his expungement, the fee has now been lowered to $300 thanks to legislative changes made in 2019.

The specifics of the fee were of importance during the hearing, as it is split between a $50 fee due when filing for expungement and a $250 fee that is due if the expungement is granted by the court.

Appearing on behalf of the state, attorney Robert Baldridge argued the expungement is analogous to a bankruptcy petition, which also requires a fee, but he also agreed that such expungements are still a unique situation.

The crux of Baldridge’s defense is that the fee is not covered under the relevant statute that allows a person, based upon their income levels, to have fees waived when they file, defend or appeal a court action. He also stated that the fee itself does not violate any constitutionally protected rights and does not create a civil rights issue.

“Regarding the constitutional implications, it’s not the fee that’s preventing Mr. Jones from owning a firearm or voting, and I am not trying to sound callous,” Baldridge said. “But he can’t exercise his constitutional rights because he forfeited them by admitting he committed a felony.”

Baldridge argued that because felony disenfranchisement is already allowed through the conviction process, the reestablishing of those rights cannot create a constitutional issue simply because of a filing fee.

In a candid moment, Justice Michelle Keller questioned Baldridge about the perceived impropriety of the fee, suggesting it could look bad that the money goes to several bodies of the criminal justice system that could have been involved in the conviction.

“We want you to make your life better, and the judge said yes you meet the criteria, felony record expunged, but yet there are these funds that go to pay back the very people who put you there,” Keller said. “I’m just struggling with this.”

“Justice Keller, we all have to live with terrible laws that the General Assembly has written," Baldridge responded.

The state's attorney continued by saying that even if there are issues with the expungement statute, the court must stick to statutory rules when enforcing it.

In his closing argument, Abate made it clear that his client is not arguing for a constitutional right to an expungement, but rather to simply be given fair access to such a remedy.

“We are simply arguing, in reference to the constitution, that if the legislature creates an expungement remedy it cannot reserve it to the people who can afford to pay for it,” Abate said.

Subscribe to Closing Arguments

Sign up for new weekly newsletter Closing Arguments to get the latest about ongoing trials, major litigation and hot cases and rulings in courthouses around the U.S. and the world.