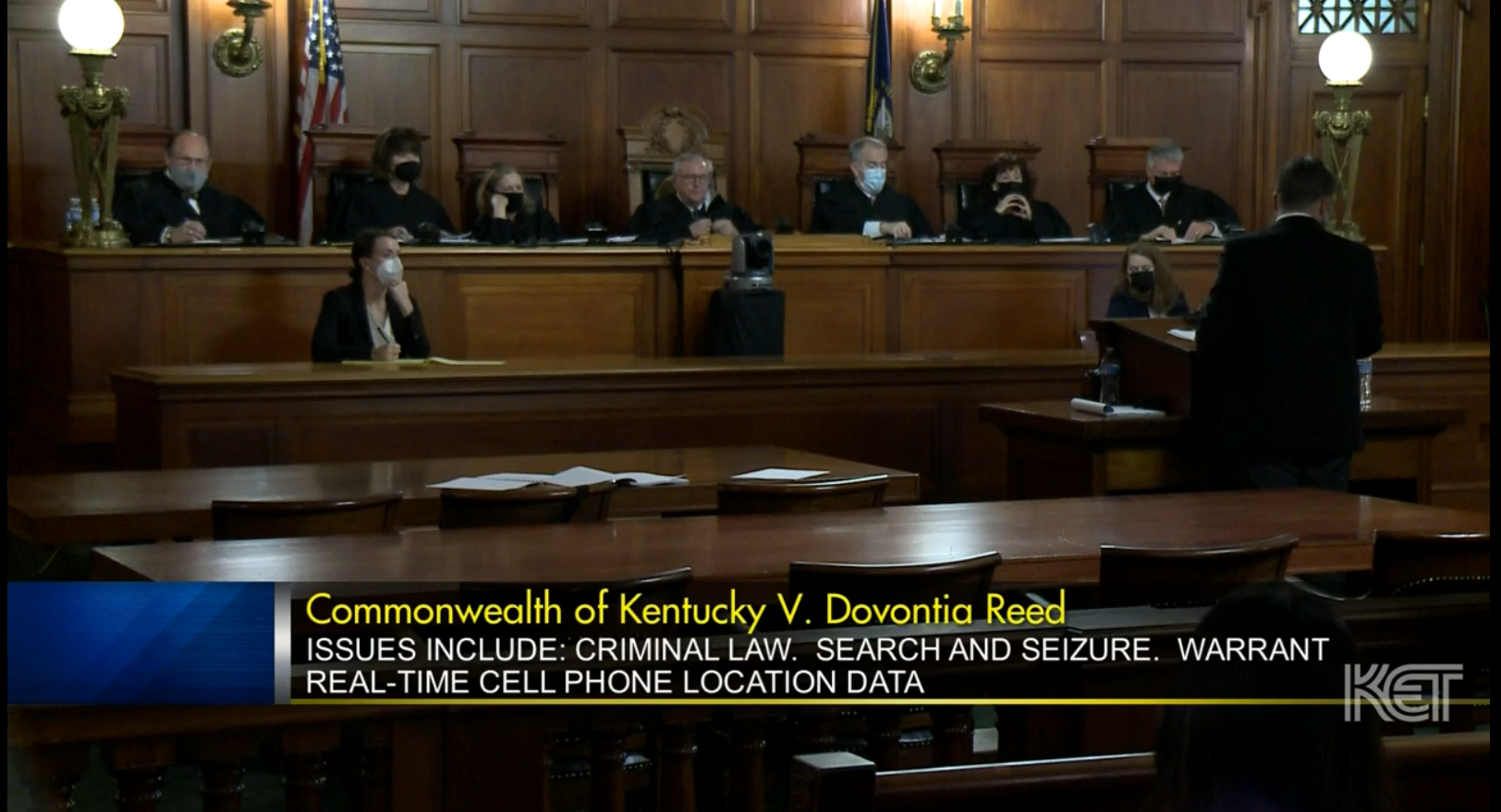

FRANKFORT, Ky. (CN) — The Kentucky Supreme Court heard debate Wednesday on whether police need a warrant to use real-time cellphone data to track a criminal suspect.

The case focuses on Kentucky man Dovontia Reed, who was arrested in April 2017 and later charged with first-degree robbery and possession of a stolen firearm.

According to court documents, Reed lured the victim, who he knew, to a gas station in Versailles, Kentucky, by calling him and asking for money. After the victim arrived, Reed robbed the man, who then called police after Reed drove away.

The victim gave the police a description of Reed and his vehicle, but most importantly gave police the phone number which Reed had used to call him. Police contacted Reed’s cellphone carrier and were able to “ping” his phone to determine his rough location, before eventually arresting him.

After being charged, Reed moved to suppress the evidence against him by claiming that police had unlawfully searched his location using real-time data without a warrant.

The Woodford County Circuit Court denied Reed’s motion, finding that the use of cellphone location data is not considered a search under the Fourth Amendment. The Kentucky Court of Appeals disagreed and ruled in favor of Reed, prompting the state to appeal to the Kentucky Supreme Court.

Attorney Brett Nolan argued on behalf of the state Wednesday and urged the seven justices to reverse the appellate court's ruling that found that the data was improperly used.

“This case presents a narrow issue that requires the court to do nothing more than apply four decades of well-established law to a modestly novel specific set of facts,” Nolan said.

Nolan went on to argue that the police were within their rights to contact Reed’s cellphone company to determine his location, which does not violate an individual’s right to privacy and is not considered an illegal search.

“All of this is important for understanding the Fourth Amendment implications of what law enforcement did in this case. The police officers did not acquire information stored on Reed’s phone,” according to the state's brief submitted to the court. “The officers did not physically access Reed’s phone in any way. Rather, the officers obtained information from a third-party -the cellular carrier - about the general location of Reed’s phone while he traveled on the highway.”

Location is a central issue in the case because the legal expectation of privacy is different in a home than while driving on a public road, which Reed was doing when police tracked him.

Justices Lisabeth Hughes and Michelle Keller questioned Nolan about that issue.

“Don’t you have to have knowledge that they are on a public road, for the public road narrow holding to apply?” Keller said.

Nolan responded by saying that according to past cases brought before the U.S. Supreme Court, the answer to Keller's question was no.

Attorney Adam Meyer, who represented Reed, argued real-time location data can only be used if police have obtained a warrant first. He said the Kentucky Supreme Court should not just uphold the ruling of the appeals court, but issue a broader decision to govern all such cases.

“This court should give clear guidance in this case and come down with a bright-line rule that if real time CSLI is needed or sought out by the government that a warrant is required,” Meyer said.

CSLI is an acronym for the type of data at issue and stands for cell-site location information.

Justice Debra Lambert expressed concerns to Nolan that it is simply a police officer’s judgment call to access such CSLI information, and such a decision does not get approval from the judicial branch in the form of a warrant before a citizen is tracked.

“Shouldn’t we be conserved about that?” Lambert asked.

“I think the concern should always be whether or not the police are violating a reasonable expectations of privacy,” Nolan said.

Nolan went on to argue that in this case the tracking did not occur in a private setting, but along a public road where the privacy expectations are different.

In his brief filed on behalf of Reed, Meyer argued that the public road element is untenable as law.

“This is an unworkable approach because the government can almost never be certain what the real-time location of a person will disclose,” the attorney wrote. “This court should decline to accept a rule that allows for real-time CSLI searches where the government hopes the person of interest is on a road.”

The justices did not indicate when they would issue a decision in the case.

Subscribe to Closing Arguments

Sign up for new weekly newsletter Closing Arguments to get the latest about ongoing trials, major litigation and hot cases and rulings in courthouses around the U.S. and the world.