(CN) — Archaeologists announced Thursday they have discovered new evidence about an ancient dinosaur that has perplexed experts for decades, proving the creatures were water-dwellers and did not have to compete with a similar but separate species for food resources.

When the Tanystropheus fossil was presented in 1852, there was much confusion over its anatomy and lifestyle. The fossil contained lengthy, hollow bones that scientists could not decide the purpose for. Initially they hypothesized the possibility of pterodactyl-like wings, but eventually figured out they were neck bones.

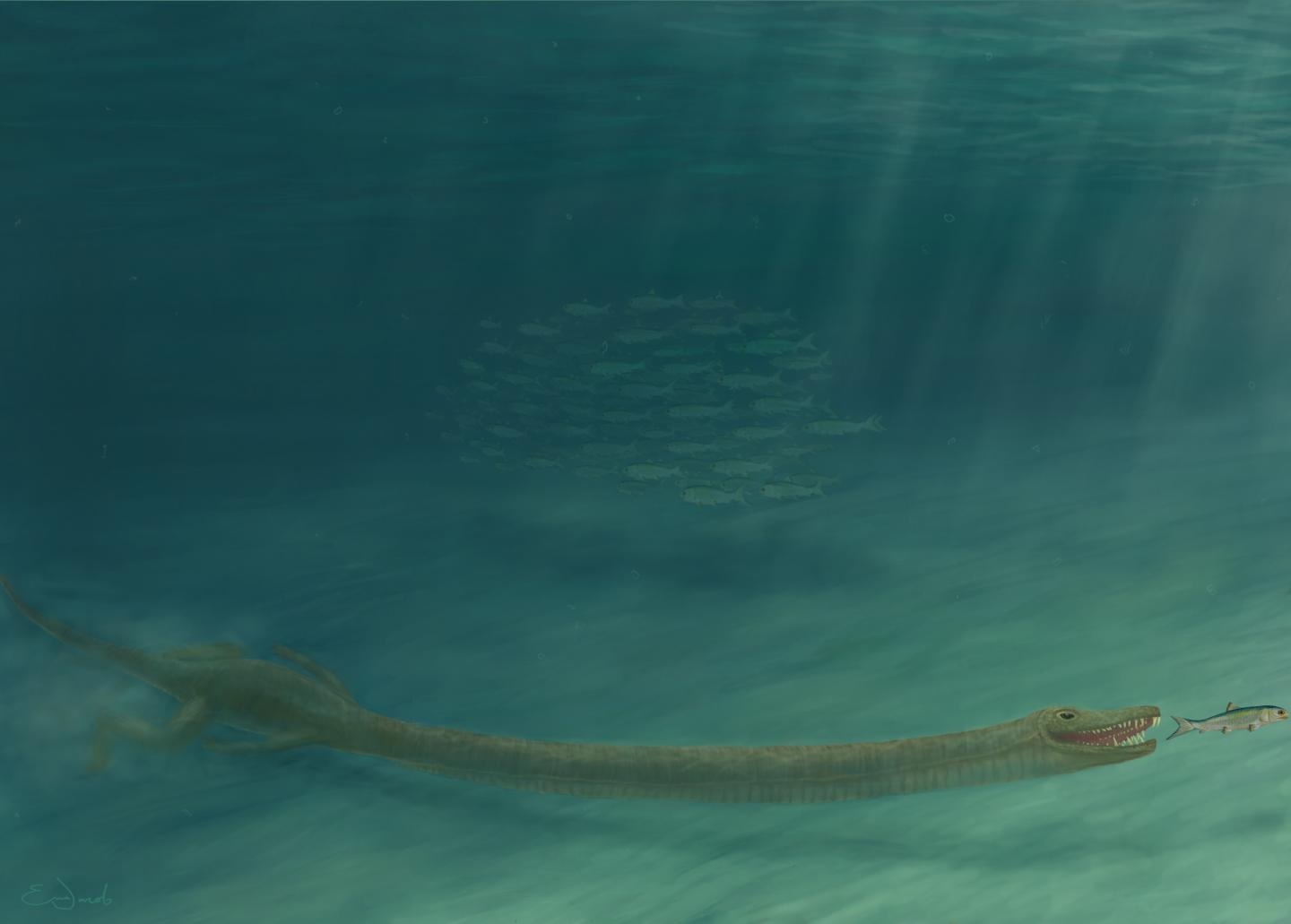

With this information, they concluded the fossils came from a strange, massive reptile sporting a 10-foot neck half the length of its entire body. Many details were still unknown however, including its lifestyle and whether a smaller Tanystropheid recently discovered was a youngling or a separate species.

In a study published in the journal Current Biology, several unknowns were finally answered when researchers performed a CT scan on a crushed skull of the fossil and made a computerized recreation. They discovered the giants were in fact water-dwellers and that their smaller counterparts were a different species that could live alongside them with little to no competition.

"I've been studying Tanystropheus for over 30 years, so it's extremely satisfying to see these creatures demystified," said co-author Olivier Rieppel, a paleontologist at the Field Museum in Chicago.

After the Permian mass extinction approximately 250 million years ago, 96% of marine species and 70% of terrestrial life was destroyed, allowing reptiles to dominate ecosystems. One of those reptiles were the Tanystropheids, who thrived in the mid-to-late Triassic period 242 million years ago.

This creature baffled scientists because its unusual body shape gave very few hints as to whether it lived on land or in water.

"Tanystropheus looked like a stubby crocodile with a very, very long neck," said Rieppel.

The dinosaur's neck was its most prominent feature. It was about three times as long as its torso and featured additional bones that made it less flexible. The authors said one interesting quirk about its neck was that it only had 13 vertebrae that were very elongated to account for the length, much like how giraffes have only 7 vertebrae. These creatures are sometimes referred to as the “weirdos of the Triassic.”

One of the pieces of the fossil discovered in this region, a crushed Tanystropheus skull, held significant answers to the many questions surrounding this species. Technological advancement in the field of digitally reassembling fossils allowed lead author and researcher at the University of Zurich Stephan Spiekman to perform a CT scan of the broken pieces and build a 3-D model of the fragments.

"The power of CT scanning allows us to see details that are otherwise impossible to observe in fossils," said Spiekman. "From a strongly crushed skull we have been able to reconstruct an almost complete 3-D skull, revealing crucial morphological details."

The rendered skull not only gave the team an image of the Tanystropheus in unprecedented detail, it also provided conclusive evidence that it was water-based. The dinosaur’s nostrils were on top of its snout, a trait seen in semiaquatic animals like crocodiles and hippos, suggesting that they would likely stand in the water and wait for unsuspecting prey to swim by. Also similar to semiaquatic animals, the authors note it might have laid its eggs on the shore.

These animals could reach upwards of 20 feet long, but archaeologists have also discovered smaller 4-foot Tanystropheids in the same region of Switzerland where the giant reptiles are often found — adding yet another mystery to this species’ track record. To investigate this, the team sought to analyze the bones to find out the age of this miniature Tanystropheus.

"We looked at cross-sections of bones from the small type and were very excited to find many growth rings. This tells us that these animals were mature," said senior author Torsten Scheyer, a researcher at University of Zurich.

The authors say this was the nail in the coffin, effectively proving the smaller creature it was a different species. They decided to name the larger of the two Tanystropheus hydroides and the smaller Tanystropheus longobardicus.

"For many years now, we have had our suspicions that there were two species of Tanystropheus, but until we were able to CT scan the larger specimens we had no definitive evidence. Now we do," said co-author Nick Fraser, Keeper of Natural Sciences at National Museums Scotland.

"It is hugely significant to discover that there were two quite separate species of this bizarrely long-necked reptile who swam and lived alongside each other in the coastal waters of the great sea of Tethys approximately 240 million years ago," Fraser added.

Furthermore, the authors deduced that due to the differences in the sizes and shape of their teeth, they likely hunted different prey and did not have to compete for resources.

“These two closely related species had evolved to use different food sources in the same environment. The small species likely fed on small shelled animals, like shrimp, in contrast to the fish and squid the large species ate,” said Spiekman.

“This is really remarkable, because we expected the bizarre neck of Tanystropheus to be specialized for a single task, like the neck of a giraffe. But actually, it allowed for several lifestyles. This completely changes the way we look at this animal," Spiekman added.

Rieppel credited this separation to a phenomenon known as niche partitioning, where natural selection will push species that would normally compete into different lifestyle patterns of resource consumption.

"Darwin focused a lot on competition between species, and how competing over resources can even result in one of the species going extinct," said Rieppel. "But this kind of radical competition happens in restricted environments like islands. The marine basins that Tanystropheus lived in could apparently support niche partitioning. It's an important ecological phenomenon."

Subscribe to Closing Arguments

Sign up for new weekly newsletter Closing Arguments to get the latest about ongoing trials, major litigation and hot cases and rulings in courthouses around the U.S. and the world.