(CN) — Florida, with a population of 22 million, is now giving public access to court complaints when they are electronically received, reinstating a tradition that existed for centuries in the time of paper.

The nation’s third most populous state joins California, with 40 million people, and New York, with nearly 20 million, in returning traditional access to journalists. Texas, the second biggest state, is currently evaluating its public access policy.

Together those states represent the four biggest in the nation. The federal courts as a matter of national policy continued the paper tradition as they switched to e-filing over the last decade.

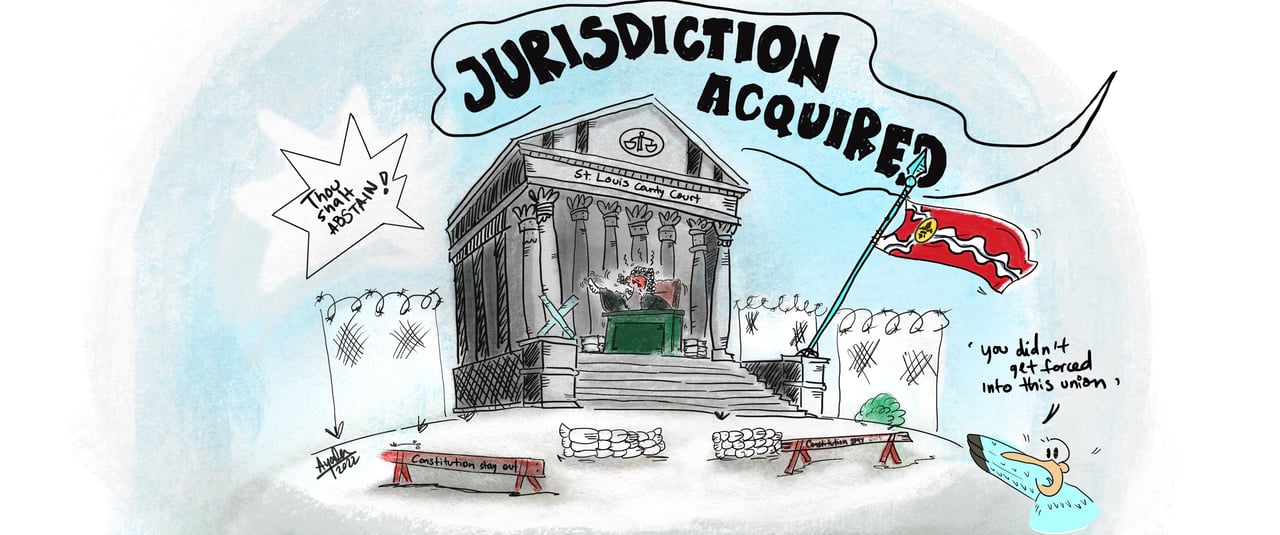

“There was a time when — and some in this room may remember it — when you took a pleading to the courthouse and the clerk stamped it physically and it went into different bins and it was available immediately,” said Eighth Circuit Judge Bobby Shepherd during oral arguments in a case against St. Louis County (Missouri) earlier this year.

The judge was referring to paper complaints that were passed across the counter at the clerk’s office. Those new complaints were often run-of-the-mill matters but on a regular basis held news of a local or national controversy. As a result, reporters looked through the box of new complaints at the clerk’s counter every day as part of their work on the courthouse beat.

Florida’s return of old-fashioned access in electronic times represents a remarkable change in policy after court clerks fought against it for six years. When the change of heart came, a new policy was put in place with surprising speed.

As a result of a federal ruling enjoining the director of Florida’s e-filing portal, her lawyers signed an agreement that said: “Florida Courts E-Filing Authority will implement a statewide public access system in the E-Filing Portal for non-confidential circuit civil complaints to be publicly accessible upon receipt, but in no circumstances to exceed five minutes.”

The deal, which became effective on September 7, gave the director another six months to put constitutionally required access in place. But, moving swiftly, the state got it done by the end of October, four months ahead of schedule. Up and down the state of Florida, newly filed cases can now be reviewed and reported on within five minutes of being received.

Courthouse News was represented in the federal litigation by Carol LoCicero with the Tampa firm of Thomas and LoCicero, and Florida’s portal authority was represented by Gregory Stewart with the Tallahassee firm of Nabors Giblin & Nickerson. In an earlier comment, LoCicero said, “Providing statewide, on-receipt access to new complaints is about accurate, timely news reporting to the public and the integrity of the judicial system itself.”

Along with Florida’s 67 county courts, 25 e-filing county courts in California give public access to the new civil complaints when received, or have promised to do so by early next year. Those courts cover 86% of California’s population. New York state courts have been letting the public see new complaints on receipt for roughly five years, along with nearly all federal courts.

On the other side of the access wars, private lawyers and state attorneys general in Oregon, Idaho, New Mexico, Missouri and Maryland have indiscriminately bombed requests for on-receipt access with every possible legal tactic and calumny. The Conference of State Court Administrators, a national group, has helped organize and solidify the opposition, where court officials pay for the fight against public access by using public funds.

But it is the men and women in black robes who have been the most powerful testifiers to a tradition that existed since time out of mind in American courts — public access right after a lawyer handed a paper complaint to the court clerk.

“What we’re saying is, ‘Oh, for about 230 years you could walk into a Missouri courthouse, into the clerk’s office, and say, ‘Hey, can I see what’s been filed today,’” said Eighth Circuit Judge Ralph Erickson, who was on the panel with Shepherd in hearing oral argument over public access in Missouri.

Both Shepherd and Erickson, the first appointed by George W. Bush and the latter by Donald Trump, had been litigators in private practice in Arkansas and North Dakota and were familiar with how it worked in paper days. The third judge on the panel, Judge David Stras, wrote the ensuing opinion reversing a judge who had dismissed a First Amendment complaint by Courthouse News.

In his opinion, Stras, a Trump appointee and former member of the Minnesota Supreme Court, wrote, “In St. Louis County, access used to be easy. Reporters could go to a bin at the intake counter in the clerk’s office and review them. When Missouri switched to an e-filing system, same-day access became the exception, not the rule.”

Courthouse News has been making that same point about other state courts for roughly 15 years.

In litigation over the same withholding policy in Texas, a similar observation was made by U.S. District Judge Lee Yeakel who worked as a trial lawyer throughout Texas before he was appointed to the federal bench in Austin by the younger Bush. At a hearing this summer, Yeakel described how the district court in Austin used to operate.

“It came in, it was pushed across the counter, it got file-marked with a hand stamp. And if a member of the press happened to be standing there and said ‘I really want a copy of that,’ they'd make that copy right away,” Yeakel said from the bench.

In turn, the way reporters used to review new complaints as they crossed the counter was described from the bench by U.S. District Judge Sarah Morrison in Columbus, Ohio. Appointed by Trump, she too worked as a civil litigator with a private law firm before going on the bench.

“When they were going down and looking at them in a stack, I mean, I remember those days, when they had them there, some sitting in the little cubicle. They were there, and that's — that's what they did,” she commented at a hearing in June.

The difference between the way it was and the way it is flows from a policy adopted by many state court clerks in the transition to e-filing. They started holding back new complaints until clerks looked over the lawyer’s clerical entries made during the filing process. The result was accurately described from the bench by U.S. District Judge Christina Reiss in Vermont. Appointed by Obama, she practiced law with a private firm in Burlington before becoming a federal judge.

“There would be no delay in an e-filing system,” said Reiss. “There could be 1,000 complaints; there could be 100,000 complaints. The only delay that's going to show up in e-filing is when you insert a staff member into it to do something else. Right? The delay is in this review process.”

She then enjoined the Vermont clerks from withholding new complaints. And they returned traditional access within three weeks.

Going back down to Florida, U.S. District Judge Mark Walker enjoined the e-filing portal’s chair and she returned traditional access in seven weeks.

Subscribe to Closing Arguments

Sign up for new weekly newsletter Closing Arguments to get the latest about ongoing trials, major litigation and hot cases and rulings in courthouses around the U.S. and the world.