Ohio’s courts, like many across the land, allowed news reporters to see paper filings when they crossed the clerk’s counter. Then when the electronic revolution finally came to those state courts, like many across the land, they took traditional press access away.

One of the clearest examples of the effects of that take-away can be seen in Columbus where the new state court cases languish in a docketing queue for days before becoming public. A local court rule declares all of them confidential — in effect a blanket sealing order — until whenever the clerk gets around to docketing them.

Challenging the take-away, Courthouse News on Monday filed a First Amendment action against Franklin County Court of Common Pleas in Columbus.

“The advent of e-filing should not erase the historical tradition of access to new civil complaints. Technology should illuminate the halls of government, not darken them,” said the memo accompanying the complaint.

The complaint seeks, and the memo argues for, an injunction against the clerk for violating the First Amendment right of access. In the two most recent decisions addressing what is called a “no-access-before-process” policy, federal judges in Vermont and Florida enjoined clerks from enforcing that policy.

The Florida injunction by Chief U.S. Judge Mark Eaton Walker forbids the chairwoman of Florida’s e-filing authority from holding back access to new court filings while the clerical work of docketing is done. The Vermont injunction by U.S. Judge Christina Reiss similarly forbids the Vermont court administrator from delaying public access until the clerical review process is complete.

The policy followed by the clerks in Florida and Vermont is the same in its essentials as the policy followed by Clerk Maryellen O’Shaughnessy in Columbus. In other words, she is denying access to the new civil complaints until the clerical work of docketing, now often called processing, is done.

In the Florida and Vermont cases, and in the Columbus case, the clerks rejected requests to provide access when the new cases are received. Rather than simply agree to return public access, they have shown themselves willing to use publicly paid lawyers to defend their withholding policies and risk the public expense of paying for this news agency’s attorney fees if they lose.

The source of obduracy is found partly in a set of yearly clerk conferences in Williamsburg in 2013. The body organizing the meeting, the Conference of State Court Administrators, was originally led by administrators who believed in public access and saw the power of electronic filing to improve public access.

But by the time of the Williamsburg conferences, the organization had been taken over by members who distrusted electronic access and who developed a philosophy called “practical obscurity.” This notion argued that paper records were hard to find -- obscure in practice – so electronic records should be too.

The belief in practical obscurity has mixed with other factors causing a rigid opposition to timely public access in the electronic era. They include the fact that state court clerks often sell public records to supplement their local budgets, and the clerks believe they are the custodians of the court records, a belief that, according to clerks themselves, often slurs into a sense of ownership.

Ohio traditionally gave excellent public access to new filings – the court record as it was created. Reporters as well as the public could review the new civil cases in a box at the counter in Cleveland, Columbus, Cincinnati, Youngstown and other locations.

Included in the First Amendment action filed Monday is a declaration by bureau chief Adam Angione who described the once-upon-a-time access in Columbus.

“In those paper filing days at Franklin County Court of Common Pleas, the newly-filed complaints were stacked on top of a desk behind the intake counter,” he wrote. “For about a day or so, the complaints remained on that desk so that the court’s official newspaper, The Daily Reporter, and Courthouse News could review and report the news of the court without delay.”

The clerical work of creating a docket to keep track of future events in the case was done later. “The next day, those complaints were sent on to the docketing clerk who entered case information,” said the Angione declaration.

A second declaration by this author describes the tradition of access throughout the courts of America. It also talks about traditional access in Youngstown and the transition to delayed access with e-filing.

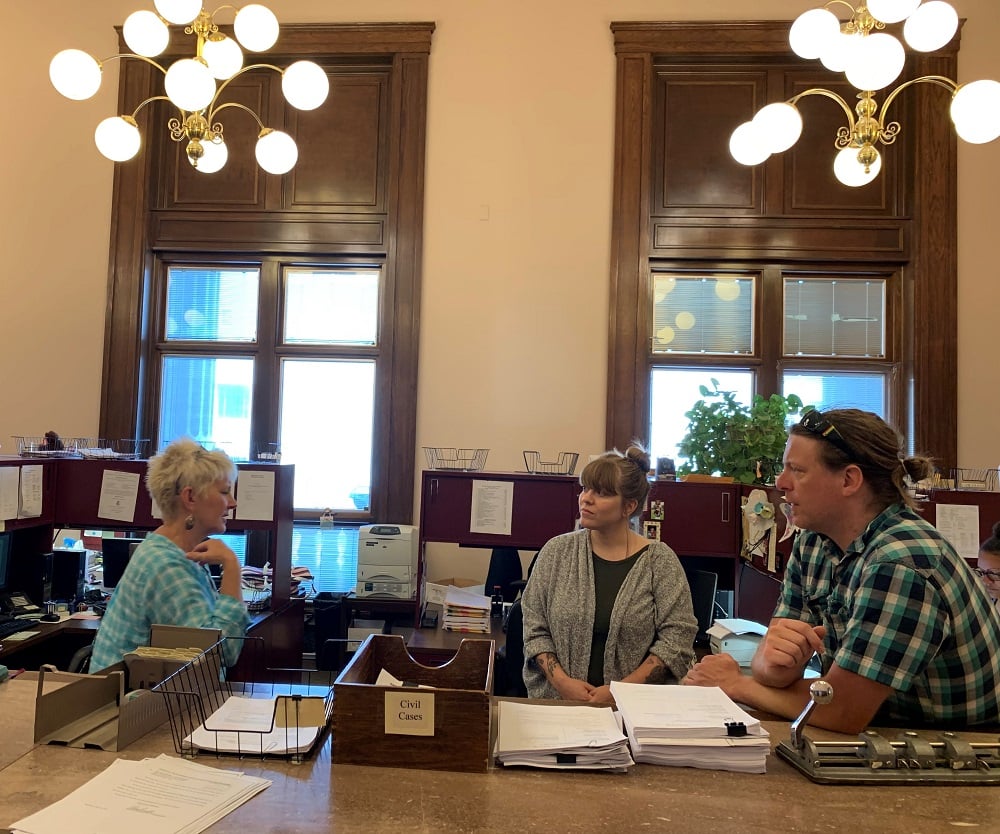

“There on the counter I saw the vestiges – what I call ‘the bones’ – of traditional access,” said the Girdner declaration. “There was a wooden box labeled ‘civil complaints’ where, in the days of paper, the new complaints were placed once they crossed the counter.”

An opinion piece about the discovery of that artifact is attached to the declaration. The synopsis for that piece says, “Accomplishing chrysalis in reverse, the court in Youngstown was caught at the moment it was metamorphosing from a traditional box-on-the-counter paper access court to a delayed access efiling court, a terrible sight to behold.”

Courthouse News is represented in the suit by Alexandra Berry and Jack Greiner with the Graydon law firm in Ohio. Early last year, they filed a similar action against the clerk in Cincinnati, over the same policy. But that case has languished. A motion to dismiss filed by the clerk more than a year ago has not been decided.

The suit filed this week in federal court in Columbus was assigned to Judge Sarah Morrison, a 2018 appointee.

The memo asking her to enjoin the Columbus clerk notes extensive delays that render the new complaints stale by the time they can be seen. Very few cases, 6%, are seen on the day they are filed. Fully 40% are withheld for three days or more with a substantial number blacked out for more than a week.

Unlike any court that this news service has familiarity with, the Columbus court has put in place a rule that declares all new civil filings confidential until they are reviewed by a clerk and docketed. “All documents submitted for e-Filing shall be confidential until accepted by the Clerk,” says the local court’s e-filing rules.

The Courthouse News memo argues that the rule and the practice of holding back the complaints restrict the First Amendment right of access. U.S. Supreme Court precedent makes it clear that a clerk cannot restrict press and public access once the right is established – unless the clerk has an overriding reason and uses the least restrictive alternative.

The local rule’s blunderbuss approach to the new filings, automatically declaring all of them confidential, cannot pass the Supreme Court test of Press Enterprise v. Riverside II, the memo argues. That is because the clerk does not have an overriding reason and has less restrictive alternatives.

Specifically, the clerk is using e-filing software by Tybera Development Corp. which also supplies the software used in Utah where the state courts automatically render the new filings public when they are received, in other words with no delay. The same is true in the federal court in the Southern District of Ohio where this week’s complaint was filed.

In conclusion, the memo says, “The public depends on the press for news and information about the judicial branch of government and thus the right of access to court filings serves an important role in the free expression of not just the press, but also the public. Courthouse News respectfully requests that Defendants be preliminarily enjoined from restricting access to newly filed civil complaints until after such complaints are processed, and that Defendant be directed to make such complaints accessible in a contemporaneous manner upon receipt.”

Subscribe to Closing Arguments

Sign up for new weekly newsletter Closing Arguments to get the latest about ongoing trials, major litigation and hot cases and rulings in courthouses around the U.S. and the world.