BUENOS AIRES, Argentina (CN) — Five million more people now live in extreme poverty than in 2020, affecting 13.8% of Latin Americans — a problem compounded by the Covid-19 pandemic, an annual United Nations report reveals.

Argentina, Colombia and Peru all recorded increases in extreme poverty of at least 7% since the pandemic, the highest in the region, climbing to levels last seen 20 years ago.

The pandemic has deepened the vulnerabilities of national health care and social systems in a region that has been the hardest hit by Covid. Home to 8.4% of the global population (653 million people), Latin America and the Caribbean has seen 28.8% of total Covid-19 deaths worldwide.

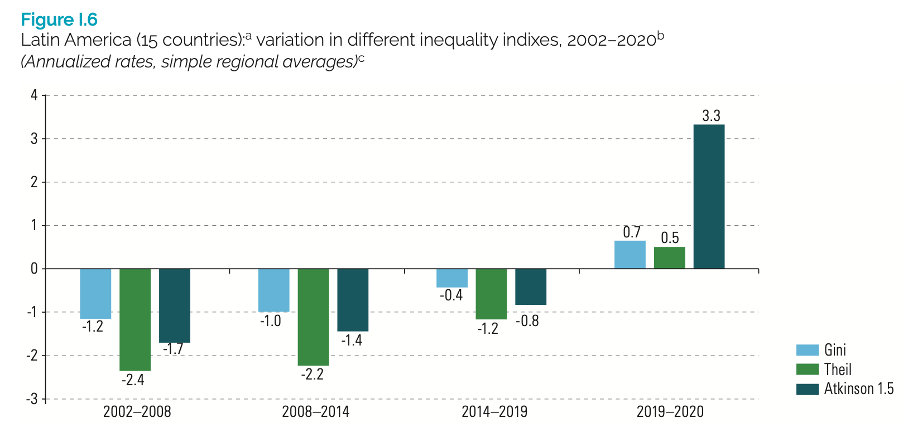

The impact of the pandemic has also accelerated economic and health care inequality in the region. Its Gini coefficient — an economic index used to measure inequity in wealth distribution — increased by 0.7% while its Atkinson index (which is more sensitive to changes in the lower sections of income distribution) rose by 3.3%. The largest increases were felt in Peru, Chile, El Salvador, Bolivia and Colombia.

In terms of vaccine rollouts, 59.4% of the region's population had been fully vaccinated by the end of 2021 — meaning the region will likely miss the World Health Organization's target of 70% by mid-2022. Yet the landscape is marked by visible inequality, with Chile (86%), Cuba (85.5%), and Uruguay (76.8%) having fully vaccinated most of their populations while Saint Vincent and the Grenadines (23.6%), Jamaica (19.1%), and most starkly Haiti (0.6%) struggle for vaccines and the infrastructure to roll them out more efficiently.

Economic inequality stretched as lower-wage jobs saw sharp declines in income while the super-wealthy got richer. “The loss of wage income was the largest contributor to the increase in inequality,” the report by the U.N.'s Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC) read. “In countries where inequality increased, the wage income of the poorest quintile plummeted by 39.4%.”

Emergency cash transfers paid by governments helped mitigate the further widening of inequality.

At the same time, billionaires in Latin America, with a combined wealth of at least $446.6 billion (or 11% of the region’s GDP), saw their wealth increase by 14% between 2019 and 2021 — albeit with sharp fluctuations. Their wealth dropped by 19% between 2019 and 2020 before spiking 41% between 2020 and 2021.

Most Latin Americans have gotten poorer since the Covid-19 crisis, with downward movements into the low and lower-middle income groups that now make up 75.8% of the population.

After two decades of progress in reducing poverty and inequality across the region, driven by labor market growth and more inclusive social policies channeled through strong commodity prices, progress has halted and even begun to unravel. “The reduction of poverty and inequality during the 2000s was primarily a result of changes in the labor market (growth in formal jobs for people with primary and secondary education, increases in the minimum wage) and, to a lesser extent, improvements in social policy,” said Diego Sánchez-Ancochea, head of the Oxford Department of International Development, and author of "The Costs of Inequality in Latin America: Warnings and Lessons."

“When economic growth slowed after 2015, maintaining the increase in formal jobs became much harder than before and social spending stopped growing as fast,” Sánchez-Ancochea said. “Those negative forces accelerated during the pandemic due to the economic crisis; in addition, the lockdowns affected many informal workers who did not have protection and could not work from home more than other groups, making things worse.”

Informal workers — temporary laborers, independent contractors and those paid under the table — young people and women have been affected most. The outflow of women from the labor market has dropped to 50% compared with 73.5% for men. Despite dropping out of the workforce, women are still more likely to be unemployed (11.8%) compared to men (8.1%), and youth unemployment rose to 23%.