WASHINGTON (CN) — No stranger to litigation during four years in office, former President Donald Trump is unlikely to see that trend end in his new civilian life.

On Tuesday, he and Rudy Giuliani, as well as the far-right groups Proud Boys and the Oath Keepers, were sued by the Democratic chairman of the House Homeland Security Committee, Congressman Bennie Thompson, over last month’s insurrection at the U.S. Capitol.

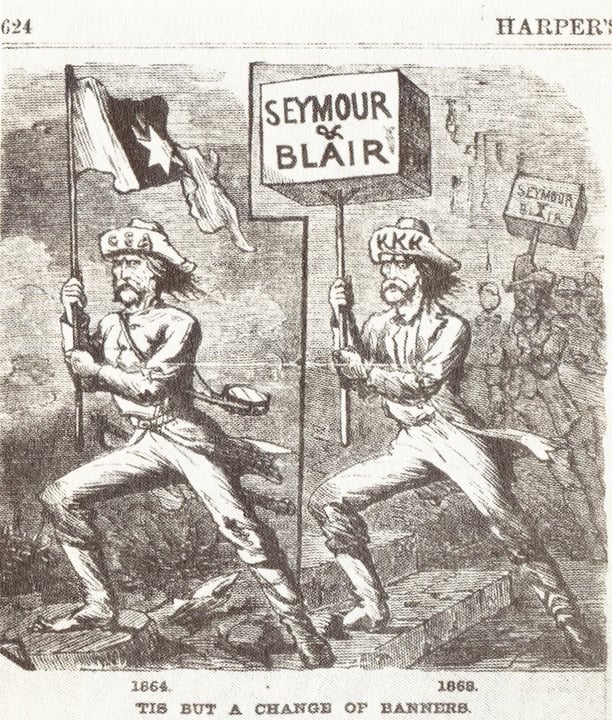

Alleging more than emotional distress or violations of federal anti-racketeering law, however, the Mississippi Democrat rests his claims on the Ku Klux Klan Act of 1871, an obscure statute adopted in the Reconstruction era to protect members of Congress as white supremacists sought to interfere with their duties following the Civil War.

Thompson says Trump conspired with his supporters in the same way to incite a riot that would keep Congress from carrying out the ceremony solidifying his 2020 election defeat to now-President Joe Biden.

More members of Congress will be joining as plaintiffs in the coming weeks, according to the NAACP, which is representing Thompson in the case.

After the Civil War and the assassination of President Abraham Lincoln, the United States was plunged into a period rife with political violence and legal retaliation against slave emancipation. The Southern Black Codes, for example, used a series of state laws to replicate the conditions of slavery by prosecuting people for not keeping a job and making children work on plantations as “apprentices” until they turn 18.

Meanwhile, the Klan was ascendant. From its founding in 1865, the group used violence to keep Black voters from the polls, intimidate members of Congress who either were Black or sympathetic to them, and terrorized Black communities. Their mission: Revolt until the Klan was in political power. With its ranks flush with members of law enforcement and community leaders, the Klan’s level of power already was not insignificant.

In 1870, South Carolina Republican Governor Robert K. Scott wrote a letter to President Ulysses S. Grant that detailed the tumult of domestic terrorism making its way through the South thanks to the Klan.

“Colored men and women have been dragged from their homes at the dead hour of night and most cruelly and brutally scoured, for the sole reason that they dared to exercise their own opinions upon political subjects,” he wrote.

One line from the letter all but calls out to the NAACP for its new case: “I am convinced that an outbreak will occur here on Friday […] the day appointed by law for the counting of ballots.”

It was some years earlier during the impeachment of President Andrew Johnson, Lincoln’s successor, that Ohio Congressman John Bingham began getting death threats from the KKK.

After Bingham and a handful of fellow congressmen approached Grant to request some form of protection, Grant between 1870 and 1871 signed three bills known as the Enforcement Acts to protect formerly enslaved people’s rights to participate in a democracy. The Ku Klux Klan Act was the third Enforcement Act.

The statute itself specifies that “if two or more persons in any state or territory conspire […] to molest, interrupt, hinder, or impede him in the discharge of his official duties … each and every person so offended shall be deemed guilty of a high crime.”

It may be a strong case in the NAACP’s favor, but not against all of the accused.

“The problem of suing Trump is that he was the president,” Indiana University law professor Gerard Magliocca said in a phone interview. “The Supreme Court held that you cannot sue the president for damages for things that he does as president that are official actions.”