(CN) — Headlines in 2016 declared that the world’s most ancient chameleon was found fossilized in amber 99 million years ago. On Thursday, researchers involved in that discovery amended their claim: that ancient amphibian was no chameleon, but a member of a now-extinct lineage of tiny, salamander-like creatures known as albanerpetontids, or “albies” for short.

“They look like a weird combination of lizards and salamanders,” said Edward Stanley, a University of Florida herpetologist and co-author of a new study published in Science Advances.

Frogs, salamanders and caecilians — limbless creatures resembling worms or slick snakes that live underground or underwater in tropical environments — are the three groups that together compose modern amphibians.

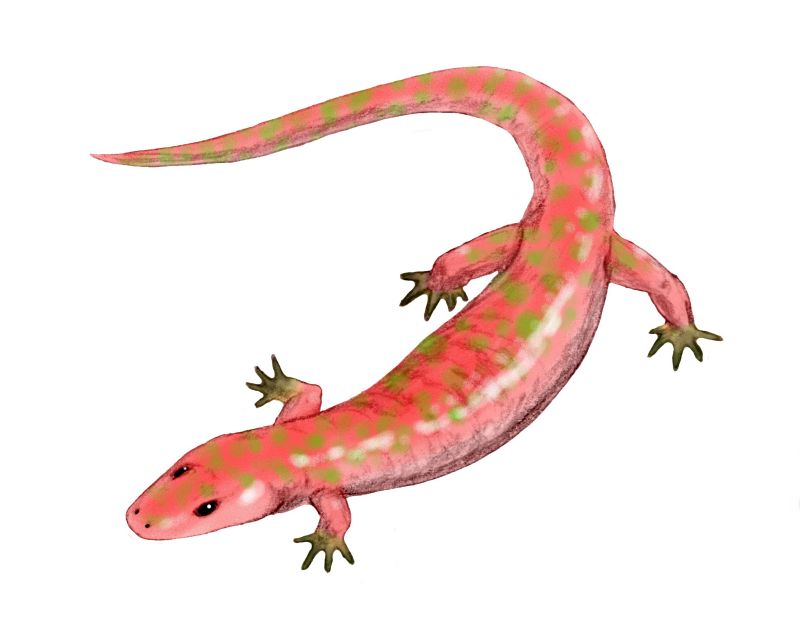

A fourth clade of amphibians, the albanerpetontids were superficially similar to salamanders: their bodies were slender, small and lizard-shaped, with four short limbs and blunt snouts and a tail. But scales were embedded in albies’ skin, their skulls were armored and those four short limbs ended in claws.

“They have a very strange neck joint that presumably allowed them to move their heads a lot more than modern amphibians do — frogs and salamanders have just a very simple joint in the back of their head that articulates with the neck,” Stanley said in an interview. “And then they had this very strange joint at the front of their jaws that’s like an interlocking mechanism between the two mandibles, that presumably allows for a lot more jaw movement.”

The albanerpetontids spanned Eurasia for more than 165 million years: their survival spanned the Middle Jurassic to the Early Pleistocene, the geological period commonly known as the Ice Age that began 2.58 million years ago. Stanley says the changing climate may have contributed to the albies’ demise, or that chameleons migrating from Northern Africa into Europe could have finished the amphibians off.

It’s no wonder they mistook the infant specimen for a chameleon: a specialized tongue bone in the albanerpetontid’s mouth allowed it to fire its tongue out like a projectile to feed, similar to chameleons’ tongue-projecting abilities.

The specimen Stanley and his colleagues studied in 2016 was too young at the time of its death to see these distinctive features. The scientists were able to verify the prior misidentification when an adult albie’s fossilized remains were found in the same region of the Myanmar tropics as the earlier-discovered juvenile.

“Most fossils are preserved in soil or sand or on riverbeds, so they’re often compressed — they’re crushed down, and lose a lot of three-dimensionality,” Stanley said. “This amber specimen is essentially just hermetically sealed in place. It has all the features exactly as they were in life.”

The team took CT scans of the fossilized remains and created three-dimensional models of the albie’s anatomy. These high-resolution images helped the team realize that they had discovered a new genus and species of albie, Yaksha perettii.

The 3D schematics of the albies’ anatomy will be freely available online for anyone to use, Stanley said.

“Other people can use it and incorporate it into their work as well. Not just scientists, but educators or people who are just interested in learning more about the world about them. That’s all available for free online,” Stanley said. “It really brings the specimens into the hands of more people than it would if it were just sitting in a museum somewhere.”

One of the first things Stanley did with the 3D data, he said, was scale the skull up about seven or eight times its size before 3D-printing a model for co-author Susan Evans, the University College London developmental biologist who first approached Stanley and his colleagues after the 2016 discovery to suggest that their “chameleon” might instead have been an albanerpetontid.

“It’s a paperweight on Susan’s desk, but I must admit I printed one out myself as well, and now it’s sitting on top of my router,” Stanley said. “It looks nice.”

Subscribe to Closing Arguments

Sign up for new weekly newsletter Closing Arguments to get the latest about ongoing trials, major litigation and hot cases and rulings in courthouses around the U.S. and the world.